The first film on the second day of the Venice Mostra was the latest offering from Yorgos Lanthimos. Once again, it’s in English, and it’s called Poor Things, based on the novel of the same name by Alasdair Gray. It stars Emma Stone, Mark Ruffalo, and Willem Dafoe. A young woman, Bella (Stone), is brought back to life by scientist and her guardian, Dr. Godwin Baxter (Dafoe). Initially naïve, Bella is eager to learn about the world around her, albeit under Baxter’s protection. Wanting to see more, she runs off with Duncan Wedderburn (Ruffalo), a slick and debauched lawyer, and travels across continents. Free from the prejudices of her times, Bella demands equality and liberation. That’s what the synopsis says.

Lanthimos has never been a favourite of mine. The first film I saw by him was Dogtooth (Kynodontas) in 2009, the week after it won the Prix Un Certain Regard at Cannes. When I look at my notes from the time, I see that I didn’t find the metaphors all that subtle and that the film felt like a pale version of Arturo Ripstein’s classic El castillo de la pureza (1973).1 Another of Ripstein’s best films was screened in the Venice Classics section, Profundo Carmesi (1996). Since The Lobster (2015), the director has, like so many other Europeans, been working in English. He has become one of many directors who make mainstream films in arthouse clothing.

Lanthimos’s style (I use the term loosely) has thus far consisted of writing mildly awkward dialogues placed in an environment with an ever-so-slight twist. It could be over-dimensioned interiors, the use of a fish-eye lens or a combination of the two. It seems enough for some people to find the films engrossing, provoking, and above all, arty. The director’s Kubrick complex is on full display. The main reason for the director’s popularity is his ability to make spectators feel that they are perfectly understanding a work with signs of complexity. If we isolate Poor Things, it seems this film managed to persuade critics who were previously sceptical of his oeuvre. The operative word in that review is “enjoy”.

Who are the Poor Things?

It’s known relatively early on that Bella is a child in a grown-up body. Initially, her behaviour is clumsy, irrational, and uninhibited in an irritating manner, like when she stabs a corpse in the eye with a scalpel. Once her mind grows a bit, her lack of inhibition will extend to “furious jumping”, which is how she labels sex. Once Bella runs away from Godwin (who she calls God. God- Godwin. Get it?) Duncan Wedderburn will take her on a geographical and physical journey. Strangely, every destination they come to looks similar, whether it’s London, Porto or somewhere else, and that brings us to the production design and, above all, the cinematography.

The film was shot in Hungary, like so many films nowadays, and many of the technicians working on the film were Hungarian, as well. In an interview, cinematographer Robbie Ryan said that the production design budget was limited but that he was impressed by their work. Most reviews have heaped adjectives like gorgeous and stunning about the look of the film. I could add that contrary to many film critics, I watched Poor Things in Pala Biennale, which is, honestly, the place where cinema comes to die. Not only is the location provisional (It’s not soundproof, for instance), but spectators are let inside even 45 minutes after the film starts, which is quite disruptive.

There are very few images in Poor Things that don’t look like outtakes from a Terry Gilliam or Jean-Pierre Jeunet film. Fans of those directors might have a head start in enjoying the mindless, ugly artificiality on display here. One could only dream about what a director like Raoul Ruiz would be able to pull off with such material. There is one scene where GOD-win sits in a blue room that looks magnificent. Otherwise, the imagery is as inept as Bella’s clumsiness during the first part of the film. The B&W still looks better than the rest of the film. It’s difficult to understand the reason to shoot in 35 mm when the film largely consists of unsightly CG-enhanced images.

Seemingly, the director’s aim was to hit you in the head with brash images with blatant symbolism. Judging from most of the reviews, it seems to have worked out. I haven’t read the novel by Alasdair Gray. While reading about it, it appears that it has a meta layer where the reader is not entirely sure which narrator to trust. There are no such subtleties in Tony McNamara’s script. The only possible meta layer in the film is that Poor Things might apply to the audience. 2McNamara penned the screenplay for The Favourite (2018) as well. He seems content with creating a suspiciously modern Pippi Longstocking, which the director places in a steampunk setting, pretending it’s a novelty.

In many ways, Poor Things is as ugly and empty as Babylon, so it makes perfect sense that the director of that monstrosity would preside over a jury that awards the Golden Lion to Lanthimos’s film. According to the festival director Alberto Barbera, the decision was not unanimous, and Hamaguchi’s Evil Does Not Exist had fans on the jury as well. It ended up winning the Grand Jury Prize. Whatever reservations I had about Dogtooth, it should be said that the director’s Greek films are significantly more substantial than the later ones.

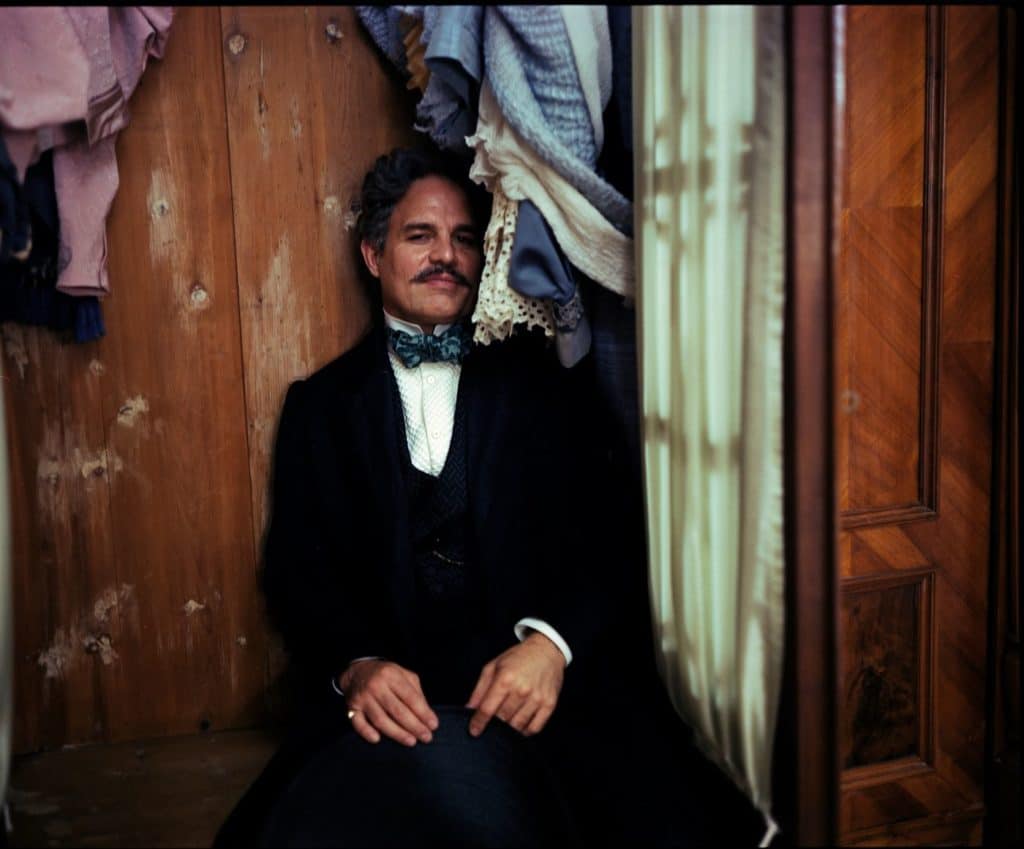

So, why is this film about a grown-up with a child’s brain so popular? I have some thoughts about that, which might materialise in a later text. As the film looks now, it plays like A Doll’s House for Gen Z. It’s difficult to fault any of the actors. Emma Stone, who is also one of the producers, throws herself into the part. Mark Ruffalo is actually funny for a while.

If anyone still feels an interest in Poor Things, a look at the trailer should suffice to thwart that.

Everything wrong with Poor Things The Disapproving Swede

Director: Yorgos Lanthimos

Date Created: 2023-09-01 03:02

1

Cons

- Simplistic

- Boring

- crass