There are not that many great directors left in world cinema. On Sunday, Alain Tanner died, and today, Jean-Luc Godard drew his last breath. I will not attempt to describe his immense legacy or the enormous impact that he had on cinema. The number of people who are influenced by him is a clear testimony of that. Quentin Tarantino named his production company A Band Apart after Godard’s Bande à part (1964). The Kaurismäki brothers, in their turn, derived the name Villealfa from Alphaville, released the subsequent year. Few other filmmakers reflected on cinema in as Godard did (Straub/Huillet obviously comes to mind). What follows are five examples (or samples?) from the director’s oeuvre.

5. Made in U.S.A 1966

Once I screened Pierrot le fou for a film class. The reactions were mixed, but most of them said things like, “How could he get money for something like this?” What those students didn’t consider was that, in those days, challenging films could actually be highly profitable. Antonioni was a highly sought-after director, and Pierrot le fou was a significant hit. Made in U.S.A was a project that started with the producer Georges de Beauregard being in debt and asking Godard to make a film for him to cover the loss.

The puzzling story of the film is inspired by American crime novels but is, above all, a direct reference to the Ben Barka affair, which occurred the year before. Raoul Coutard supplies eye-popping cinematography, and Anna Karina shines in the last feature she made with Godard. She would later appear in a segment of Le Plus Vieux Métier du monde (1967). The film is dedicated to Nicholas Ray and Samuel Fuller.

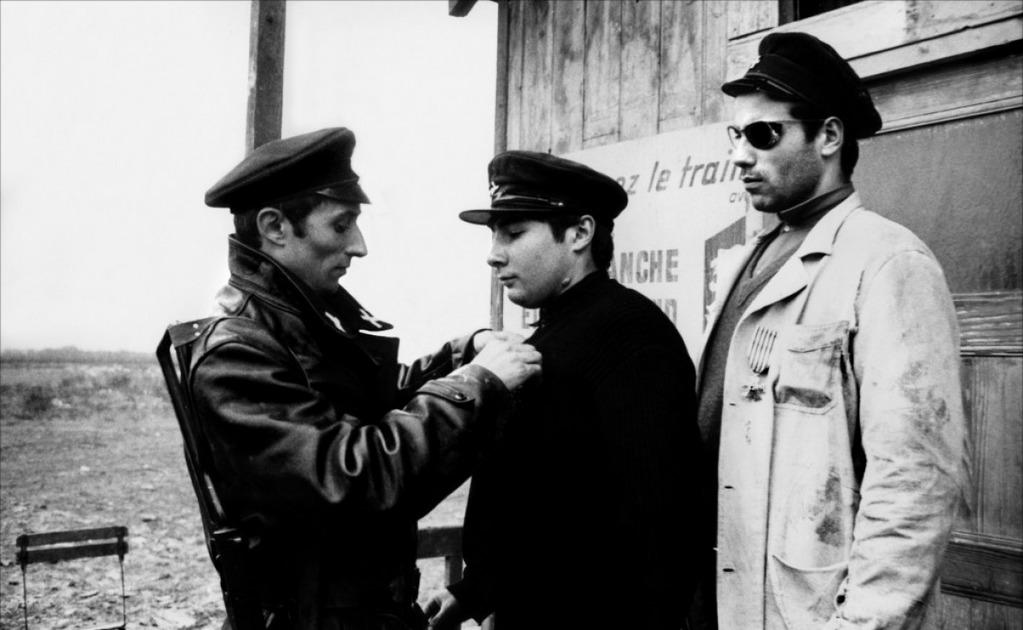

4. Les Carabiniers 1963

Les Carabiniers was Godard’s fifth film, following the highly successful Vivre sa vie. If the latter was praised by critics, Godard’s stylised version of war in Les Carabiniers rather made the critics draw fire against the director. He decided to fire back in a methodical fashion. Here are some examples.

France-Observateur (Robert Benayoun): “Godard wallows in his own mire by using over-exposed photography.”

Paris-Presse (Michel Aubriant): “He takes it upon himself to exalt lousy photography into a system.”

Candide (anonymous): “A film shot wild, where each image reveals the director’s supreme contempt for the audience.” L’Express (Michel Cournot): “A badly made, badly lit, badly everything film.”

Godard: Les Carabiniers was shot with Kodak XX negative, which is currently the best stock on the market for density, as sensitive as the old Plus X, as fast as the old TRI X, and with a better definition: it’s, in short, the best all-round stock, acceptable to both Richard Leacock and Russell Metty, the one which can “take it”, as technicians say when demonstrating its range. This negative was developed with infinite precision by the G.T.C. laboratories at 10inville, under the direction of M. Mauvoisin, who, a few years before, was the first to put a special bath at our disposal for treating the Ilford HPS of A Bout de Souffle and the Agfa Rekord of Le Petit Soldat.

The positive prints were simply made on a special Kodak high-contrast stock. This treatment was necessary to obtain, rightly or wrongly, the same photographic quality as the early Chaplin films, with the black and white contrasts of the old orthochromatic stock. Several shots, intrinsically too grey, were duped again, sometimes two or three times, always to their highest contrast, to make them match the newsreel shots, which had themselves been duped more than usual. As for Coutard, after five films with me, he has already won his third Grand Prix for photography.

Thus, Godard didn’t just whine about the criticism but actually showed how meticulously everyone involved worked on the look of the film. The abstract depiction of the war is almost Jancsóesque in its approach, if not in cinematic style.

3. Numéro deux 1975

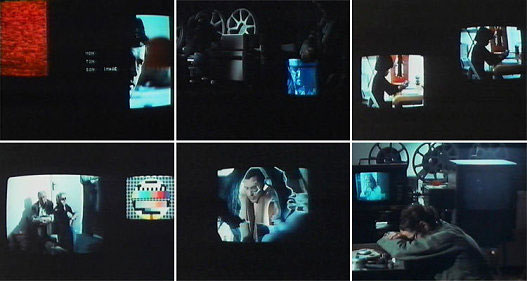

Numéro deux was shot on video and was announced by Godard to be a remake of A bout de souffle (1960). Whether that was a joke or a ploy to get financing is not entirely clear. Suffice it to say that the film bears little resemblance to the director’s first feature. What story there is revolves around a family whose illnesses might reflect on the society they live in. The man has problems achieving an erection, and the woman suffers from constipation. The latter metaphor was also used in the aforementioned Tanner’s Jonas qui aura 25 ans en l’an 2000, released in 1976.

Most of the film is displayed with a split screen, with only the top left and lower right corners displaying the action. It is a challenging watch in many ways (especially on a small screen), but some regard Numéro deux as one of Godard’s most rewarding works, and I count myself among those.

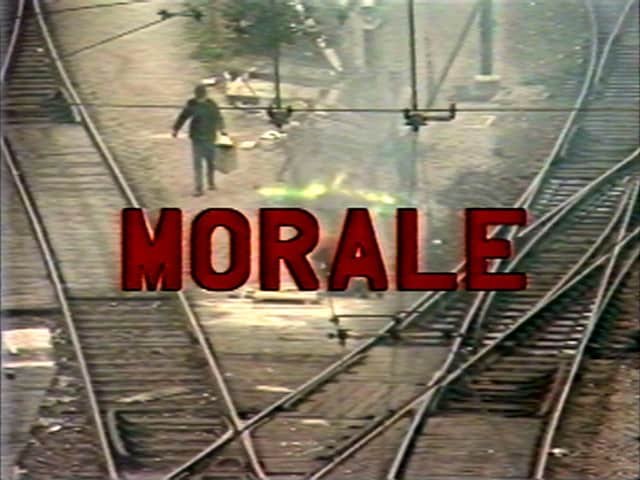

2. France / tour / détour / deux / enfants

France /tour/détour/deux/enfants was a TV series made 1977-1978 with frequent collaborator Anne-Marie Miéville. The gist of it might feel like Godard asking weird and/or unusual questions to two children. One of the themes is the way that school raises/indoctrinates children, but the most intriguing aspect of the series (no, I won’t use the m-word) is the aesthetics with the use of freeze frames and slow motion. A style that would become even more pronounced two years later in…

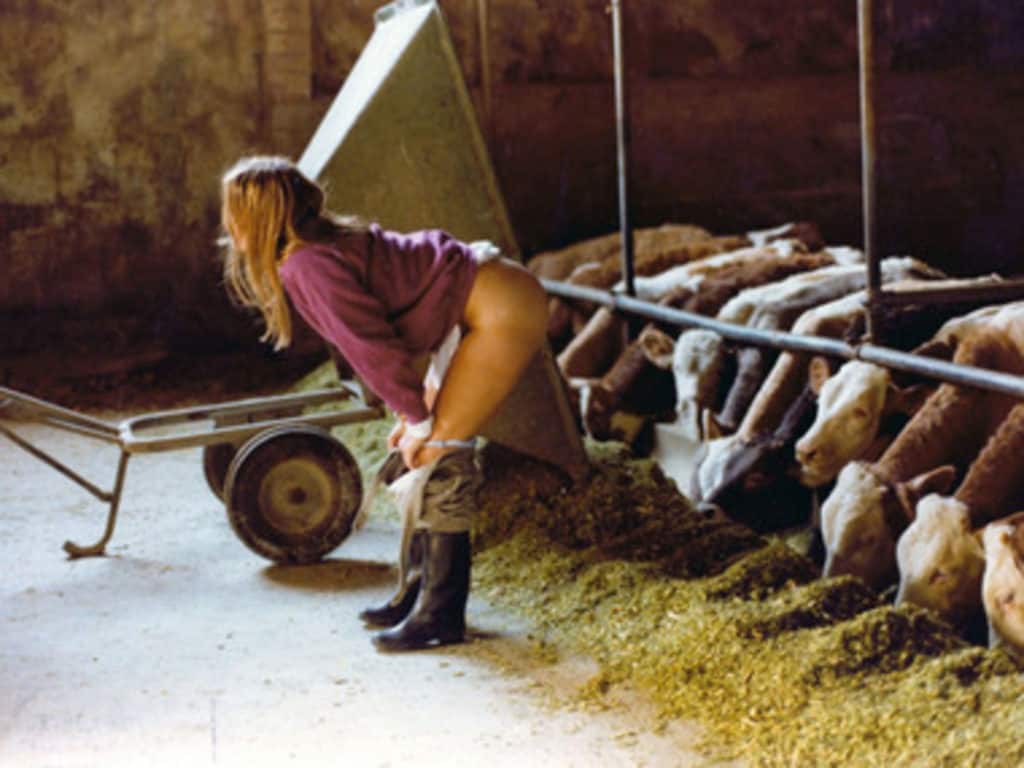

1. Sauve qui peut (la vie) 1980

After eschewing “commercial” cinema throughout most of the seventies, Godard returned to more standard fare in Sauve qui peut (la vie). Exactly how commercial the film was can be debated, but it featured stars like Nathalie Baye, Jacques Dutronc and Isabelle Huppert. Baye (who won the César for best supporting actress) and Dutronc plays a troubled couple, Denise Rimbaud and Paul Godard. Paul was the name of the director’s father. Huppert portrays a prostitute who goes through some humiliating experiences but still seems to see the men as victims This is Godard at his most incisive and cruel, with strong performances by the female thespians. This happens to be my personal favourite of Godard’s films.

A sentiment that was not shared by Christine Pascal, who painted a vicious profile of Godard in Zanzibar (1989). Her husband, Robert Boner, was one of the producers of Godard’s film and was ostensibly not happy with the experience. In many ways, the film is set around a male-female contrast where the latter seems to come out on top and be the most humane, as well. Baye’s award was well deserved. In 1981, Godard released Sauve la vie (qui peut), which was an essay on cinema based on the previous film. Two years later, Prénom Carmen won the Golden Lion in Venice and was more commercially successful.

This is obviously just a fraction of Godard’s lesser-known films and is merely aimed to display that there is much to enjoy besides the most famous classics.