Jean Cocteau wrote the play The Human Voice (La Voix Humaine) in 1928, and it premiered in 1930. Since then, it has been performed in numerous iterations. Anna Magnani’s rendition in Rossellini’s L’Amore (1948) and Ingrid Bergman’s in 1965 are famous examples. Recently, several adaptations have been made, including one with Rosamund Pike in 2018, directed by Patrick Kennedy. A Canadian production surfaced in 2019.

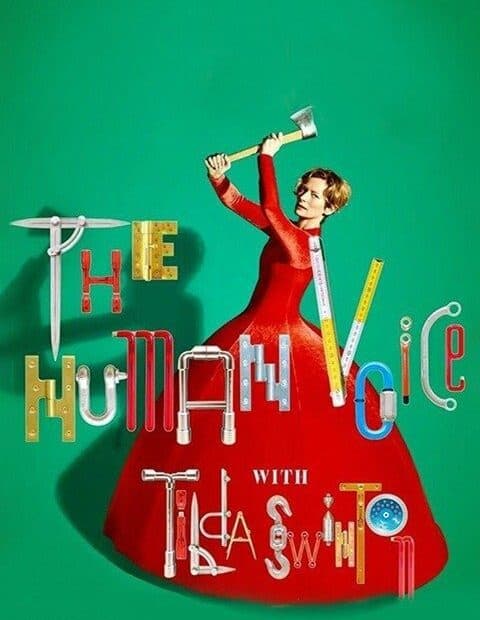

In 1958, Francis Poulenc turned the play into a highly successful opera. Initially written for Denise Duval, one of the strongest performances of the piece was by Swedish soprano Elisabeth Söderström in 1974. Last year, Pedro Almodóvar’s version was screened at the Venice Film Festival with Tilda Swinton portraying the abandoned woman talking on the phone with her former lover.

An Operatic Performance

It’s not difficult to imagine the opera when you watch Swinton’s performance. Not known for being toned down or subdued, this role is no exception. Initially, we see her in a red dress, walking around on a vast soundstage. She sits down, suddenly all in black, including her feet, while the swelling music we heard at the beginning gives way to electronic tones. Then, the credits appear with letters formed by tools, which makes sense since the subsequent scene shows her going to a hardware store to buy an axe. Upon return, she goes through her DVD collection, where we see the expected films by Sirk as well as Neon Bull, but also Phantom Thread and Kill Bill.

The Last Action Heroine

The opening credits read “Freely based on Jean Cocteau’s play.” The hardware store scene alone makes that clear. The woman in this version is not a mere victim talking on her phone but ready to take action of some kind. In that respect, it fits nicely into the zeitgeist of today. So does the phone call itself, which the woman conducts with AirPods, which makes her free to roam around her luxurious apartment but also makes it look like she’s talking into thin air. It’s not clear if there actually is someone on the other side of the call or if she is talking to herself. With Tilda Swinton in action, the answer to that question is not that relevant.

A set on the verge of a Momentous Breakdown

Almodóvar has never been a stranger to artifice. Here, it’s present not only in the larger-than-life character but also in the set design. Occasionally, the camera adopts a bird’s eye view to display that the apartment is a movie set on a soundstage. Items are also shown to be props. Still, the director doesn’t explore this more profoundly. It could be an illustration of the world Swinton’s character creates in her mind, where the only genuine creature seems to be the lover’s dog. This is Almodóvar’s first film in English, and he found the perfect thespian for his style. She dives head-first into the material with the heart on her impeccably tailored sleeve.

Ne Touchez pas la Hache!

She has an axe to grind but is too lazy to grind her coffee. Instead, she resorts to capsules for the coffee machine—one of the appliances in the apartment that isn’t merely a prop. The opening credits letters are formed by tools on a green screen, including an axe. Later, we will see a green screen hanging on the soundstage. Thus, motifs are in play, but not much is made of them during the 30-minute runtime. Swinton has acted with numerous foreign directors, notably in Béla Tarr’s The Man from London (A Londoni Férfi 2007), where she was dubbed in both the Hungarian and the international versions. Here, her own voice is loud and clear.

The film is constantly gorgeous to look at. The set decoration by Almodóvar regular Vicent Diaz and the costume design by Sonia Grande ensure a visual treat. There are numerous references to previous Almodóvar works, which also come through in Alberto Iglesias’ score. It is well known that Cocteau’s play was the basis for Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (Mujeres al Borde de un Ataque de “nervios”1988). With the colours dialled up to 11, the whole enterprise comes off as an exquisite piece of expensive candy or an equally costly liquor shot. It should be seen in a cinema, if possible.

In cinemas, the film is often followed by a pre-recorded conversation with the director and his star. Addendum: That was the case during the 2020 screenings