Four years after the release of Friss Levegö, Ágnes Koscis second film saw the light of day. Pál Adrienn premiered in the Un Certain Regard section at the Cannes film festival in 2010, where it won the FIPRESCI Prize. In the film, we follow the obese Piroska, who works as a nurse at a hospital terminal ward. She seems quite miserable and has difficulties standing up for herself at work. She lives with Kálmán who cares mostly about his diorama and his job.

One day a new patient arrives at the hospital called Adrienn Pál. The same name as one of Piroska’s best friend at school with whom she later lost contact. Now she decides to find out what happened to her and visits as many people as she can to find clues. However, many of the reactions she gets doesn’t confirm her own memories and are often contradictory to one another.

Deadly Boring Ritual

The film begins with interiors from the hospital. The first scene shows Piroska in an elevator going up from the morgue to the patient’s floor. We follow her out from the elevator while she’s dragging the, now empty, bed behind her. While the sound from the old Spica radio in the elevator fades away, we hear the clomping of her clogs.

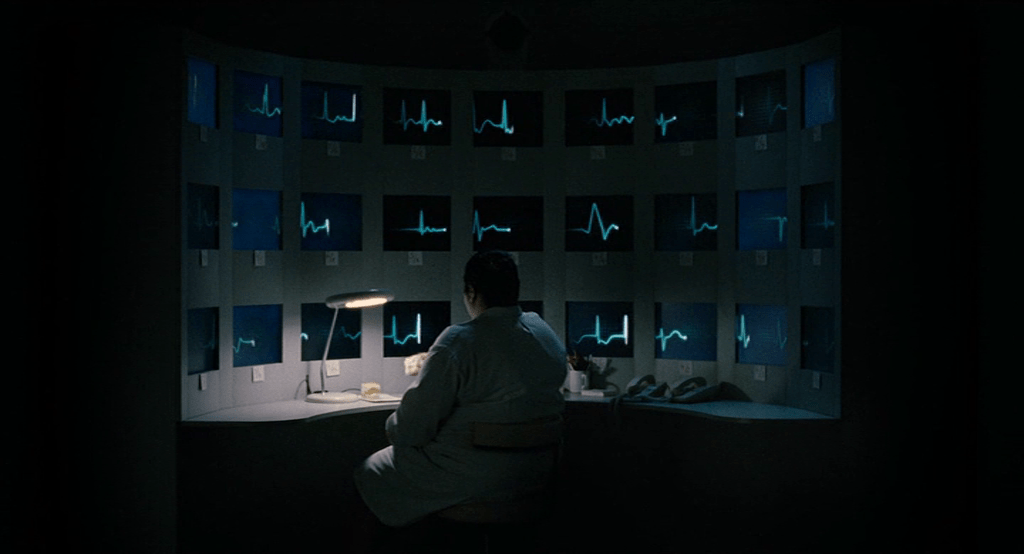

It’s a sound that will be frequent during the first part of the film. Then we cut to the workstation where we see the nurse sitting in front of three rows of screens that monitor the ECG of each patient. The repetitive sound from those displays, as well as the sound of Piroska’s clog shoes, will be the aural representation of the rut that she is in.

An alarm sounds, and it’s time to see, yet another convalescent. Once there, the doctor declares the patient dead and tells Piroska to notify the relatives. In the elevator down to the morgue, she eats a piece of pastry, and it’s not the first one we see her eating. She leaves the body in the morgue. Before she goes out, she turns off the light, and there is a direct cut to her lying in her bed at home, suggesting that her domestic life is as dull as here working one. Her bed with its grid is also similar to the beds we’ve already seen in the hospital.

A Formal Affair

Hopefully, my lengthy description of the beginning paints a picture of a film which revels in the use of sound. Since Ádám Fillenz came back after Friss Levegö as cinematographer, it goes without saying that the lensing is topnotch as well. Initially, the camera follows the protagonist through the hospital’s narrow corridors with its drab green colours. Together with the sound design, the effect is quite hypnotic, even though it depicts something dreary.

Around thirty minutes into the film, there’s a scene where Piroska enters a cinema. While taking a seat, she asks Kálmán what happened. The answer is a laconic “nothing”. That echoes the sentiment of some of the critics when the film opened, in particular the Anglo-Saxon ones. One reviewer claimed that “it’s practically impossible to buy into the premise emotionally” even though “lensing, sound and production design are topnotch.”

The film is undoubtedly, intentionally, low on story-telling, but formally it’s one of the more formidable efforts of the previous decade. Comparisons have been made with Aki Kaurismäki and even Roy Andersson. Still, I would go further and suggest that the formal splendour on display here is equal to Jacques Tati’s in Playtime (1967). One example is when Piroska pays a visit to a former schoolmate who is now quite wealthy.

The camera starts outside the flat when she rings the bell, then follows her inside as the woman talks about her affluent, indolent life, tracks backwards through a corridor that is a stark contrast to the one in the terminal ward, to end up in the vast living room. They sit down in front of some glass doors with someone walking behind it like a shadow theatre, the immensity of the space is enhanced by the sound of whistling and broken glass off-screen. Later, she will meet an interior designer in a fancy space with a spectacular view. Piroska looks around uncomfortably during the numerous interruptions, caused by the phone calls he takes.

A later scene shows Piroska sitting on the tram. At first, it just seems that we are watching her in front of us facing the camera. When the camera moves left, we understand that it is, in fact, a reflection and that she was sitting with her back to us. Once the camera finishes its movement, we see a double reflection. If one is so inclined, one could see this as an image of her journey and that looking for Adrienn will eventually end up with her seeing herself differently.

Diegetic Music gets a Full Score

Unlike the first feature, there was no music written for the film. Instead, all the music heard is diegetic, and it’s used to great effect throughout the film. Kálmán regularly listens to classical music full blast, while working on his diorama. In a sequence that runs for two minutes, the camera follows a model train through the diorama landscape to end up with Piroska sitting behind it silently following the train with her eyes.

There are other effective, and sometimes hilarious usages of music as well, whether the location is a nursery home or a karaoke club. The most beautiful use of music occurs during a child’s birthday party in a scene that defies the notion that the film would lack emotion. It’s also a setting that is very colourful. In general, the film becomes more saturated in the second half when Piroska’s world seems to open up and become livelier.

It should be pointed out, that for all the cinematic brilliance that the film displays, it wouldn’t be the masterpiece that it is, without Éva Gábor in the leading role. She is virtually in every scene, and she’s consistently perfect. It was her first role ever, and she embodies Piroska in a way that makes it impossible to imagine anyone else playing the part. In a smaller role, we see Izabella Hegyi from Friss Levegö playing a rookie nurse, learning the ropes.

Favourite films are always the hardest ones to describe. Again, I feel I hardly scratched the surface of this fascinating work, and I left out several pieces of the puzzle to avoid spoilers. Hopefully, I managed to stir the curiosity of the reader enough to watch this endlessly rewarding film.

Pál Adrienn can be watched legally on Vimeo.

Pingback: Max von Sydow dies at 90. Remebering the great iconic actor.

Pingback: Trailer for Éden By Ágnes Kocsis - The New, Great Trailer 1