István Gaál is a director who enjoyed significant success with Current (Sodrásban1964), about a group of young people on a hot summer day. Shot by Sándor Sára, the film won plaudits for its lyrical style that eschewed simple narration. It was named one of the 12 Best Hungarian Films 1948-1968 by Hungarian directors and critics in 1969. The following year, The Falcons (Magasiskola 1970) appeared. It won the jury prize at Cannes, received good reviews, and is now considered a classic of Hungarian cinema. It is based on the eponymous short novel by Miklós Mészöly, which was released in the fifties but appeared in a second edition in 1967 when it earned some recognition.

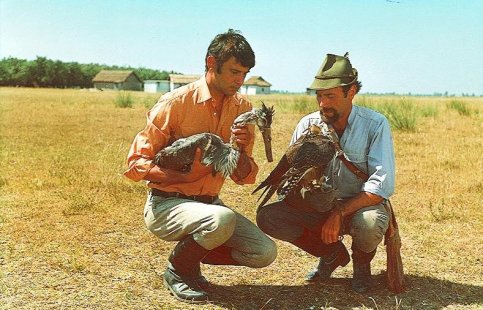

The storyline is quite simple. Fiú arrives at a falconry farm where he will study how falcons are trained to kill birds that ruin the crops. He is greeted by Lilik (György Bánffy from Jancsó’s Sirokkó), who will show him the ropes regarding the fascinating world of falconry. Lilik constantly refers to Davlah Tamyur as an authority on the topic. Along with Fiú (whose real name is Gábor Somosköi which was deemed too long), we will follow the rigorous rituals that go into the training of the birds. Actually, everything is under the strict control of the leader. An exception is his girlfriend, Teréz, who seems to sleep with whomever she feels like at any given moment.

The Perspective of The Falcons

The Falcons is generally regarded as a parable of a society under oppression. There are lines in the film that seem abundantly clear, like when Lilik talks about how a leash must have the perfect length. If it’s too short, the bird will feel trapped and not free. On the other hand, if it is too long, that’s not a good thing either since the bird wouldn’t be able to handle too much freedom. However, the film is short on dialogue and should not be reduced to being a work about a specific political situation. It aims toward a more profound statement about the complex interplay between freedom and order.

The book is written in the first person, with the visitor providing the narration. As Gábor Gelencsér has pointed out, Gaál chose different cinematic tools to convey the atmosphere at the farm. He is involved in every part of the process. He was the editor of his films and occasionally operated the camera well, such as in the famous bird training sequence here. There is a striking use of framings within the image, with doors and windows opening and closing while the camera moves, seemingly looking for open space in the closed surroundings. The music was composed by András Szőllősy. Not only a lauded composer in his own right but also the creator of the Szőllősy index.

If the index was used to catalogue the works of Béla Bartók, the film induces a similar ambience to his works. The soundtrack plays a pivotal role here, both Szőllősy’s eerie music and the sound effects with the screeching birds and the humming electrical wires. The latter creates an effect akin to Antonioni in L’Eclisse or Il Deserto rosso. The cinematographer was Elémer Ragályi, who is still working and lensed 1945 and Budapest Noir in 2017 at the age of 78. This was his (and Gaál’s) first film in colour. They took full advantage of the possibilities, and colours are very consciously used throughout the film. The military grey hues of the farm inhabitants contrast with Fiú’s bright colours.

The film runs a mere 81 minutes but manages to pack a lot into that brief running time. With its timeless themes and stunning formal qualities, this is a work to be seen and rewatched. The Falcons was digitally restored in 2012 and can now be experienced in its full glory at Eastern European Movies.