The Brazen (Bezkaunīgie) is the latest feature by Aik Karapetian. When Helena and her family revisit her late entomologist father’s summer house, tensions simmer beneath the surface. While renovating the house to become Helena’s dance retreat, they unleash a swarm of insects, igniting a struggle for survival and rekindling old family wounds. As they battle both the creepy crawlers and their own resentments, an unexpected twist forces them to confront their tragic past and fight to preserve their family bonds. The film starts sonically in a lecture room where Rihards (Didzis Jonovs) is teaching a psychology class, discussing the meaning of the word shame. (The original title means Without Shame) Meanwhile, we see his wife, Helena, attending a Zumba class.

Already, in the first scene, we have the man and wife in different spaces, one intellectual and the other more intuitive. The sequence is set to Arthur Honegger’s third symphony, more precisely, the third movement called Dona Nobis Pacem (Give us peace). Rihards’ class concerns couple’s therapy, and he invites a female student to reenact a session. Then, he puts forward the idea of giving future clients the chance to act out situations. One student suggests that it should begin in a car. When he is asked who is driving, the answer is, “The husband, of course”. Then, we see Rihards driving a car with the two children and Helena to the aforementioned summer house.

Who is The Brazen One?

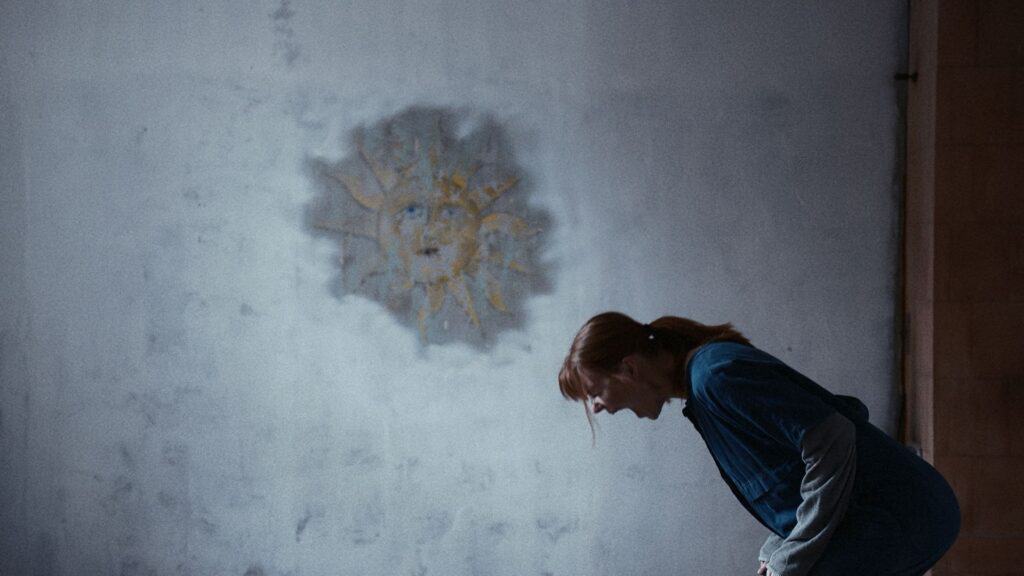

The house is in dire need of renovation, but the couple have opposite ideas of how to proceed. Helena stands in a room with a pictorial sun on the wall. She suggests they should paint the whole place blue “so the dancers will feel like they are in heaven here”. The husband rejects the idea and states that white would make the room look more spacious, and tells his wife to be practical and stop dreaming. Then, things start going south quickly once the insects are discovered. Add a confused teenage son and a previously deceased child to the mix, and the stage is set. Stage may be the operative word here. The theatricality of the piece is constantly enhanced.

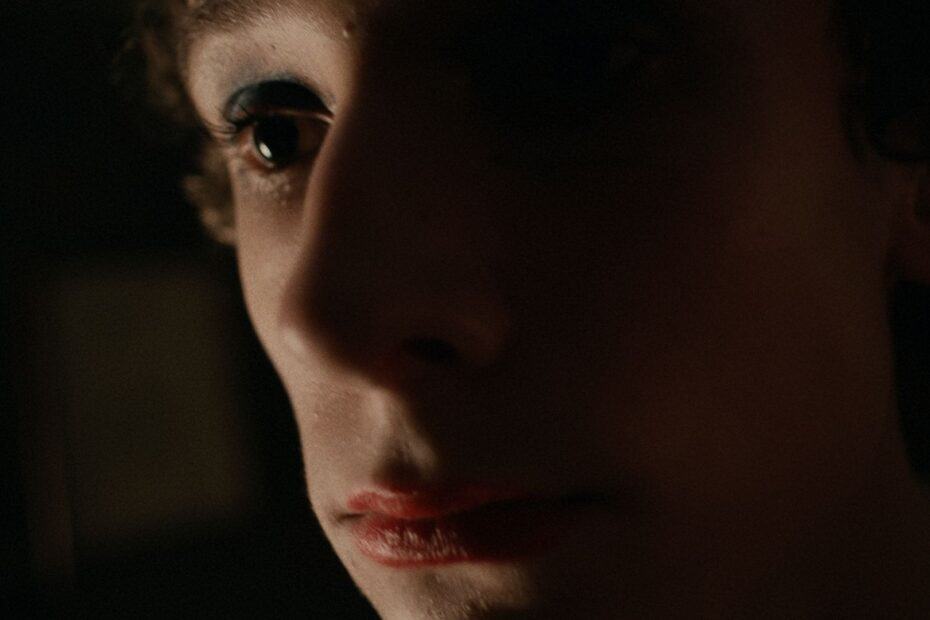

Rihard’s lecture bookends the story of the summer house, making it feel like a fairy tale. Honegger’s powerful music (written directly after WWll as a strong appeal for peace) further intensifies the feeling of something oneiric. When I interviewed Karapetian, he said that he was initially sceptical about using the music suggested by his co-writer Justine Klava but found the unmerciful tone of the symphony suitable for the film. The most important factor for The Brazen’s success is the splendid cinematography by Jurģis Kmins. It’s the second collaboration between him and Karapetian after Samuel’s Travels (Samueli rännakud, 2021), and together, they defy the low budget and deliver a highly impressive work.

During my interview with Karapetian, he referenced works like Polanski’s The Tenant (1976), Żuławski’s Possession (1981), and the Suspiria remake (2018). When it comes to the use of music, he mentioned Kubrick’s The Shining (1980). Though Possession was an obvious reference for me, I kept thinking about Manoel de Oliveira’s Le Couvent (1995), not merely because of the picture of the sun on the wall of an abandoned space but also for its usage of Sofia Gubaidulina’s music. Regarding the dichotomy between nature and civilisation, that doesn’t necessarily have to be a divide between the two genders. Thus, my mind also wandered to Jagoda Szelc’s first feature, Tower, A Bright Day, where the poles are represented by two sisters.

In an early scene, Rihards refers to couple’s therapy as a safe space. That might also be a description of the cinematic experience. Nobel laureate Harry Martinsson once referred to cinemas as the “chapel for people who are afraid of living.” The text in question, written in 1941, aimed to elevate literature over cinema. The Brazen is an excellent example of a film you stumble upon during the Black Nights Film Festival. It was actually a last-minute switch, and I am happy that I was able to watch this accomplished film in a cinema. The film unquestionably belongs to the horror genre, but maybe it could fall into the category Mark Kermode lovingly refers to as elevated horror.