Tamara (2004) is Szabolcs Hajdu’s sophomore effort, following his debut, Sticky Matters (Macerás ügyek 2001), which I haven’t seen. Tamara is set in the Hungarian countryside where Demeter Játékos (Domokos Szabó) lives with his wife, Bori (Ágnes Anna Kovács). Their relatively peaceful and lacklustre life is interrupted by the arrival of Demeter’s brother, Krisztian, and his girlfriend, the titular Tamara (Hajdu regular, Orsolya Török-Illyés). The latter feels out of place in the rural surroundings. She is quite stylish, although she wears a hammer in her elegant handbag. Her arrival (more than Krisztian’s) creates a rupture in the status quo that was taken for granted before she appeared. All the ingredients for a jealousy drama are present.

The film starts with aerial views of the village where it takes place. The colours are a bit off (or more than a bit), and animals provide the narration in an incomprehensible language that warrants Hungarian subtitles. The score feels hardly naturalistic either, and from the start, the spectator is warned that this is not an ordinary trip to the cinema. The style persistently cries out for attention, but not in an obnoxious way. The 75 minutes running time ensures that the work never outstays its welcome. Demeter is a photographer, but when we meet him, he seems to have suffered some kind of breakdown and is going through a creative crisis.

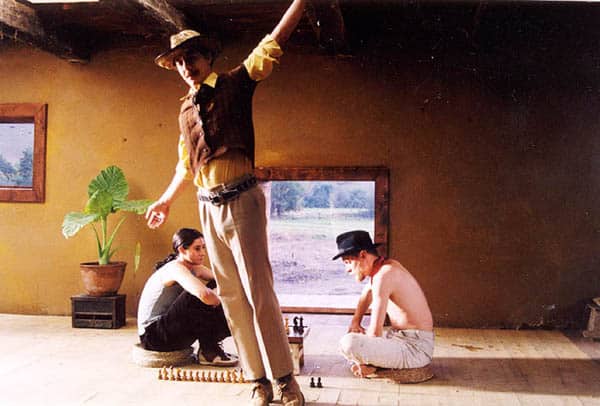

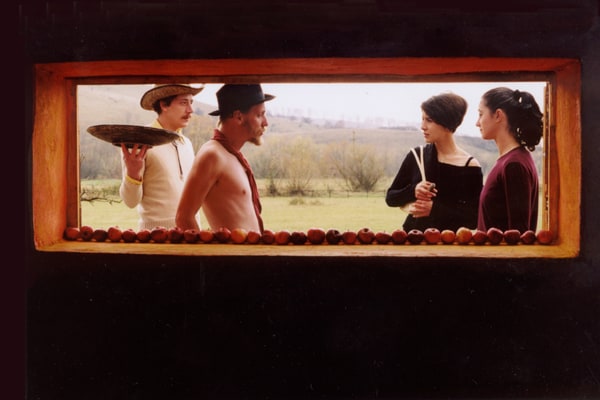

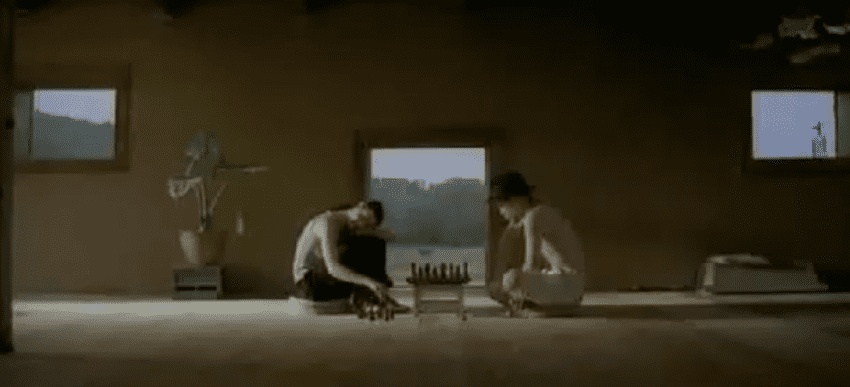

There are some mysteries in the film, like why the wooden floor in the house suddenly has small holes. Is it some tiny animal or some other presence? Mainly, the film is not preoccupied with these things or even with the upset of the balance caused by the arrival of Krisztián and Tamara. This is rather a film where stylisation takes the front seat. One of the film’s stars is Mónika Esztán, the production designer who made the costumes, as well. Combined with István Szaladják’s lensing, the quirky style sometimes becomes reminiscent of certain films from the sixties, like the Czech New Wave or the works of Skolimowski.

The story was originally a play, and the production design displays the film’s theatrical roots. The set has several windows that serve as viewpoints for an audience rather than being beneficial for the characters. If Demeter Játekos doesn’t live up to his name (Játekos means playful), the creative crew of the film certainly does. With the aforementioned references in mind, the film still has its own skewed originality. When Tamara’s hammer finally comes to use, it’s part of a satisfying conclusion, at least to the form. It might even be the perfect date film.

The subsequent career of Szabolcs Hajdu

Hajdu’s career would take a sharp turn in 2006 with White Palms (Fehér tenyér). The story about a Hungarian gymnast that suffered through abusive training as a kid is based on the director’s brother, who also plays the part in the film. When he moves to Canada to teach, he will, in some ways, continue the vicious cycle of violence when he gets frustrated. The film became an instant critical and commercial success with its slick style and is the work that the director is primarily associated with. My choice of film for this text is an indicator of my preference.