Sound Eroticism (Egézséges Erotika1986) is the first film directed by Péter Tímár. He is also known as an editor and a special effects designer. The film is set in the fifties in a crate factory. The boss, Falkay, is part of the all-male management, but all the employees are women. There is no demand for crates, but it doesn’t really affect production since it’s in the communist days. One day, a fire inspector (Róbert Koltai) arrives, and one of his ideas is to install video cameras everywhere for security. This includes the female worker’s locker room as well. Suddenly, potential buyers swarm the factory, and they are all treated to videos with the employees in different states of undress.

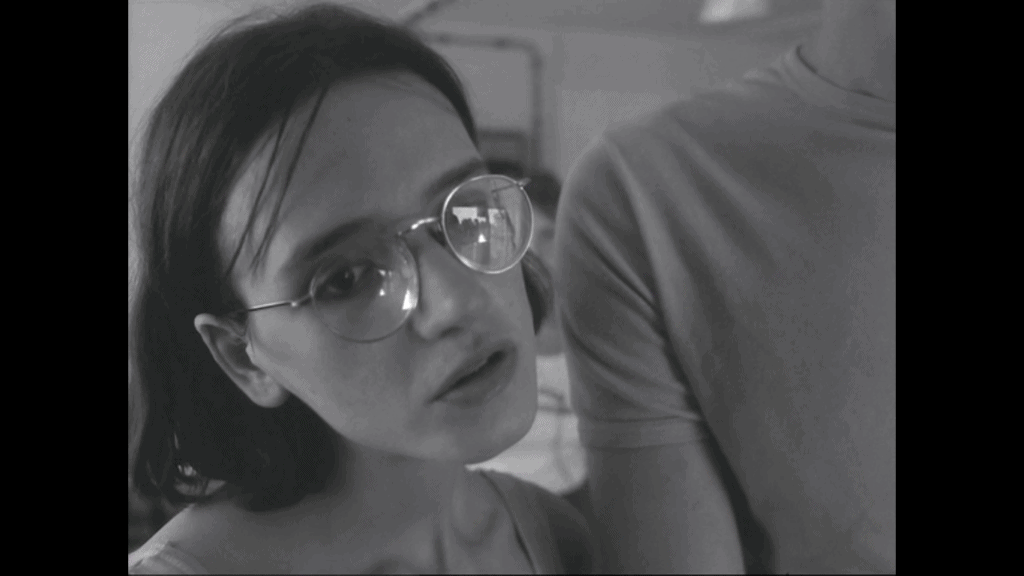

The women in the film are far from hapless victims. Falkay’s secretary Ibike (hilarious Kata Krístóf) is just one example of a woman with her own agenda and desire. Another one is Hajdúné.1 The né suffix refers to when a Hungarian woman marries and adopts her husband’s first name with a né at the end. At the beginning of the film, we see some sociologists enter the factory, presenting Falkay with a survey on women’s situation and sexuality. Among other things, they claim that it’s “Scientific-Socialist Sexuality in a nutshell” and “Materialist research on libido”. Hajdúné refuses to fill in her form. When Falkay confronts her, she says that the “socio-lists” are a load of crap.

The Sound Eroticism

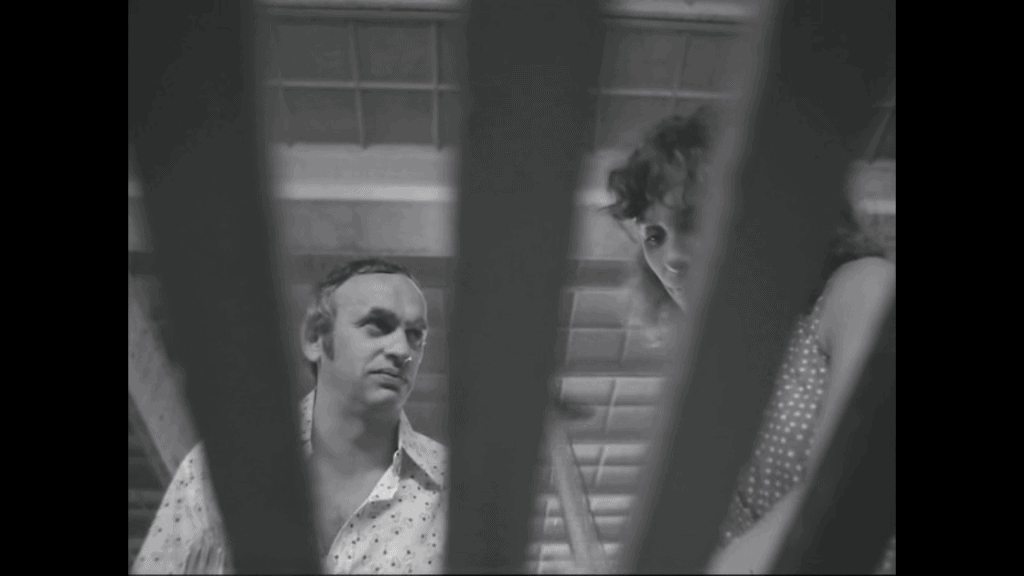

Tímár’s script is full of that kind of puns. A substantial bulk of it probably gets lost in translation, and with my limited knowledge of Hungarian, I will not pretend that I get most of it. That being said, the dialogue is a constant source of amusement. It is also delivered with weird, distorted voices. The film’s most characteristic traits are in the cinematography and how people move. A large portion of the film was shot backwards, with the actors being forced to act that way. When the projection is reversed, the outcome is a quirky, jerky motion scheme reminiscent of silent films. The satire of the Kadar is evident. There are some remarks about 1956 as well.

The film is lensed by Sándor Kardos, who was never a stranger to experimentation, as evidenced by films such as Eldorádó (1988) and Álombrigád (1989). Tímár had been in the effects business since the early seventies, working on films such as Cha-Cha-Cha, Time Stands Still and countless others. His ability is on full display here. Another distinctive work is his third film, When the Bat Ends His Flight (Mielött Befejezi Röptét a Denevér 1989). Apart from the visual methods described above, there are also numerous angular shots and distortions in the cinematography.

Favourite films are always the hardest to describe. The film is a big cult favourite in Hungary and is a work that should be experienced. It was recently restored and is available on Filmio.