Pelikan Blue (Kék Pelikan) is the first feature by Laszló Csaki and has been dubbed the first Hungarian animated documentary. It begins in 1985 when Hungary opened its borders and made it possible to travel outside the Eastern Bloc. In 1987, the world passport was introduced, and Hungarians could start using the Dollars and D-Marks many had secretly assembled through different methods. For those without Western currency came the option to exchange Eastern Marks for D-Marks. That meant that if you went to the state-run IBUSZ or other places and bought East-German Marks, you could go to Germany and triple the value of your money. That is how the three protagonists of the film met.

A man named Ákos had enough money to clean the IBUSZ office of their DDR Marks, but he took pity on the people behind him in the queue and only took half of what he could have taken. A few days later, Ákos is on the same flight to Berlin as two of the guys that were behind him in the line, Laci and Petya. They become friends and realise that they have the same passion for travel. They hear about someone forging tickets and decide to buy one. However, the quality is subpar, with misspellings and other errors. They decide to try to make counterfeit tickets themselves instead.

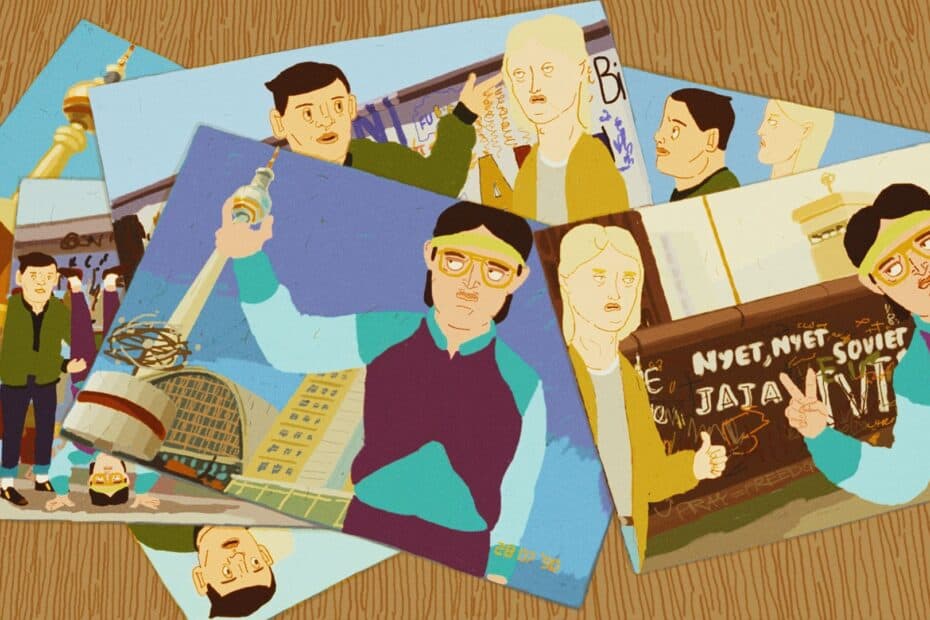

Pelikan Blue carbon paper

From here on, Pelikan Blue will go into wonderfully nerdy detail in the process of manufacturing those tickets, largely by buying the cheapest tickets and changing the destination. The film’s title refers to the fact that Pelikan Blue carbon paper was the simplest to forge, whereas Pelikan Black was virtually impossible. Then, the covers of the tickets were needed as well, and we will also follow in detail how they were taken with the help of a bicycle rim. One of the characters says, “The best period was between 1987 and 1990.” He also adds that he had never felt that atmosphere of togetherness since then. This is an interesting observation about Hungary at the time.

As described by András Török in numerous articles and books, the years before 1989 were significant since many of the Eastern European traits were slowly disappearing. One example was the lists of best authors/directors, etc, that were typically divided into an “official list”, which were the names that the government thought should be there, and the “real list”, which were the names that critics actually thought were the best ones. What happened in the late eighties was that these lists started to overlap progressively and eventually became the same. As a character says in the film, lecturers started to talk about what they had always been interested in. There was a scent of freedom in the air.

Pelikan Blue is based on interviews made with Hungarians who, in one way or another, were involved with the ticket forgery, some of them forgers but also mere customers. What happened was that people started talking about the fake tickets, and slowly, it became a business. It started humbly with a girl who wanted to check on her boyfriend in Paris but quickly escalated from there. So many young people wanted to travel but didn’t have the means to pay for a ticket. In an early scene, Ákos enters the beautiful Nyugati station. While he is there, Csaki cuts to a shot of a bird who is trying to get out but constantly hits the ceiling.

The metaphor is not as obvious as described since the shot is held for a mere five seconds. That’s just one of many examples of the carefully balanced visual language in the film. The mix of animation and live-action works marvellously, and the director manages to convey the exhilaration of young people who suddenly feel that the world is their oyster. As someone who spent time in Hungary during those years, the film brings back memories, not only of the train tickets and the numerous times I passed the border station Hegyeshalom but also of the atmosphere at the time. As I stated in my piece about Jancsó’s The Round-Up, not everyone was as enthusiastic as these youngsters.

Pelikan Blue is an extraordinarily rich film which packs a lot into its 80-minute running time. Emotional as it might be for me that was somewhat present at the time, that is obviously nothing compared to how the film will resonate for anyone who lived in the former Eastern Europe. In any case, the film is strongly recommended to anyone who wants to learn not only about the period but about the human condition in general.

Seen at the Black Nights Film Festival, where the film had its world premiere in the Critics’ Picks section.

Pelikan Blue by Laszló Csaki - The Disapproving Swede Great

Director: Laszló Csaki

Date Created: 2025-09-19 10:36

4.25

Pros

- Paints a picture of Hungary during monumental changes

- Great animation

- Local, yet universal