Ildikó Enyedi’s latest film, The Story of My Wife, will play in competition at this year’s Cannes film festival. It’s not the director’s first visit to Cannes. Her debut, My Twentieth Century (Az én XX. századom), appeared in Cannes in 1989 in the Un Certain Regard section, where it won the Camera d’Or for best first feature. I first saw it on Swedish state television, which had the habit of obtaining three films per year from the festival in those days. As I already recounted, I wasn’t that fond of it then. It struck me as too whimsical and literally all over the place. That last point still stands.

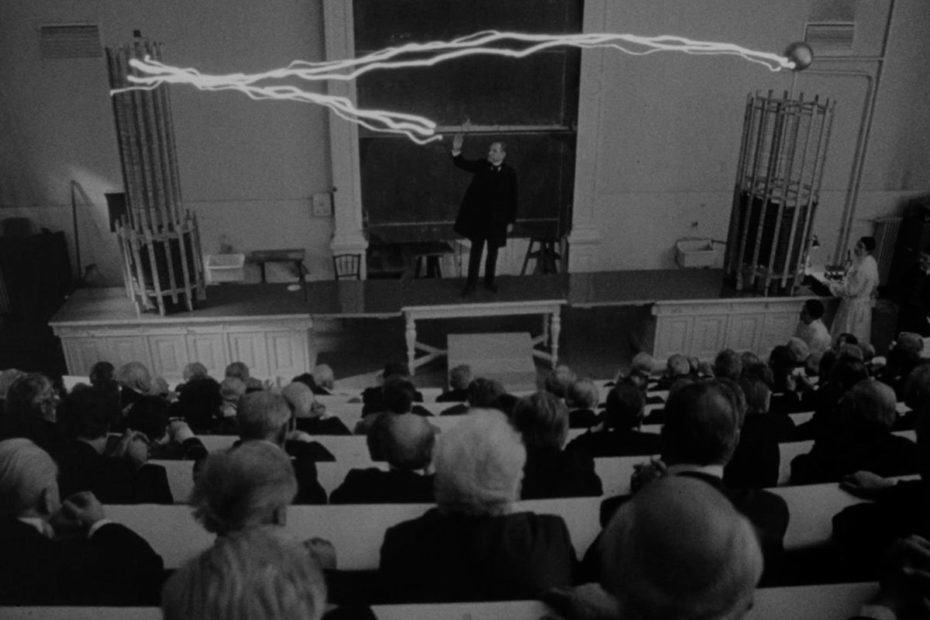

During the first 15 minutes, the film jumps from New Jersey to Budapest to continue to Paris, from where it jumps to Hamburg via Burma. After that, we are treated to a scene at the Orient Express, which one of the characters will board in Austria. It’s James Bond-level or Christopher Nolan style, to use a more topical reference point. The main difference being that the scenes are not there to advance an ordinary plot. The closest we come to a storyline in the film concerns identical twins Dóra and Lili (Dorota Segda, brilliant in both parts), who are born in 1880. Their birth is juxtaposed with Thomas Edison inventing the light bulb the same year.

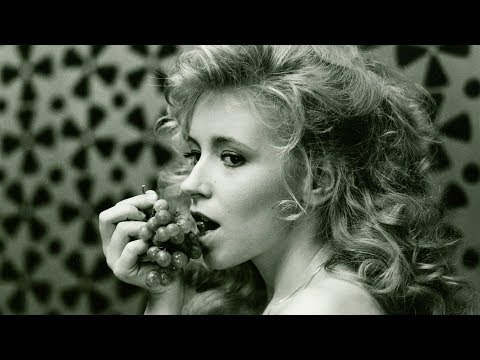

One of the first scenes shows a marching band where all the musicians are wearing bulbs on their helmets. Next to them, we see a wistful Edison (Péter Andorai) Through two stars that serve as some kind of narrator we jump to Budapest to see the birth of the twins. They will later be separated, following their mother’s death, and will come to lead strikingly different lives. Dóra will become a skilled courtesan, while Lili will end up as a revolutionary. In one scene she is given a birdcage by a man with the most fake-looking beard this side of Robbe-Grillet’s Trans-Europ Express (1966)

Trans-Europ Express

My Twentieth Century

To reveal more of the many storylines wouldn’t result in spoilers as much as it would be fairly irrelevant. The film is, in many ways, the sum of its various digressions. Discussing the film with a fairly famous Hungarian critic at the time, I lamented the fact that the film had so many titles explaining where we are. Then he added “and still it has no structure”. I agreed. More than three decades later, It’s easier to enjoy all the film’s virtues. The stunning cinematography by Tibor Mathé is much more evident in the restored version than it was on my 28″ TV set back then. The music by Laszló Vidovszky sets a fairy tale mood right from the start.

The themes of Enyedi’s work are vast in scope and filled with opposites. The most obvious ones being male vs female, light vs darkness and science contra nature. In a hilarious sequence, philosopher Otto Weininger holds a lecture in front of a group of suffragettes, including Lili. While he tries to hold a scientific lecture, the women scream that they want voting rights. He explains that he is for women’s rights but adds that women are intellectually and morally inferior to men. From a cinematic perspective, it’s interesting to note that he is interpreted by director Paulus Manker, who would make Weininger’s Night the subsequent year with himself in the titular role. His first feature, Schmutz (1987) is also worth seeing.

Not My Twentieth Century?

The film was one of the last films made in Hungary during the Eastern European days, and it looks like a film that wasn’t short on resources. It’s a work brimming with ideas, and possibly some trimmings wouldn’t have hurt, but it’s a more rewarding work than I gave it credit for at the time. The concepts might be too extensive for a relatively short film, but it’s still a work with ample rewards for a spectator today. The film ends with an enigmatic scene that might depict progress.

I still feel that Enyedi has grown as a director since then, and I can’t wait to see The Story of My Wife, which is only her sixth feature in 32 years. A Golden Palm would look great on the shelf, next to the Golden Bear. The film is available at Eastern European Movies.