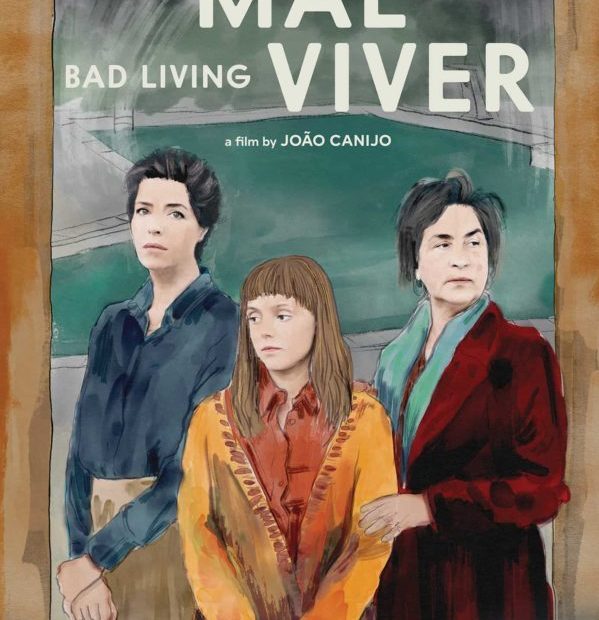

Apart from Szürkület, which was presented in the Berlinale Classics section, the greatest films of the festival were the two tandem films by João Canijo, Mal Viver (Bad Living) and Viver Mal (Living Bad). When I interviewed the director, he said that Mal Viver was his best film so far. That’s a strong statement from the director of La noite escura and Sangue do meu Sangue. There are a few of his films that I haven’t seen, but it’s easy to agree with the director in his assessment. Mal Viver was presented in the competition, while the counter film was screened in the Encounters section.

The synopsis goes like this: Five women are running an old hotel, trying to save it from inexorable decay. A long-standing, perhaps irreparable, conflict weighs down on them: they are mothers who are unable to love their daughters, who in turn are unable to be mothers. That is what the Berlinale description looked like, but is that the sensation you get when you watch the film? Four women run a hotel. Sara (Rita Blanco) seems to be the boss, and she is helped by her two daughters, Piedade and Raquel. There’s also a chef, Angela, who is involved with Raquel, who, on the other hand, is not a stranger to trysts with hotel guests.

Suddenly, Piedade’s daughter Salomé arrives, whose father died four days earlier. When Piedade sees her, she reacts like she has seen a ghost, and the initial hug is awkward at best. The awkwardness is reinforced by her simultaneously holding her latest lapdog, which she clearly holds higher in regard than her daughter. When the women later dine together, the dialogue constantly overlaps, and there seems to be a severe lack of communication, at least of the constructive kind. When Piedeade talks to Salomé about how she used to cut her hair, the latter snaps that the scissors were terrible and hurt her scalp. That is just a taster of the painful memories which will be unearthed.

The space of Mal Viver

The women are apparently trapped with each other, and no matter how vast the hotel appears, they still seem to share the same cramped space, and the misery is impossible to Overlook. Sara’s anxiety has trickled down or infected her daughter and granddaughter. In many ways, it’s a claustrophobic situation, seemingly with no exit. This is conveyed through the dialogue that has been worked out with the actresses over an extended period. However, the most important collaborator is still the cinematographer, Leonor Teles. Seven years after her Golden Bear with Balada de um Batráquio, she returned to Berlin with Canijo’s diptych.

The director said that he finally found someone who speaks the same language and called it a truly artistic collaboration. Their mutual formal research splendidly comes to fruition in the two films. In Mal Viver. The cinematography could warrant a separate analysis. Teles mostly uses static long shots which are meticulously framed. Occasionally, the speaker is outside the image, which makes the viewer share the experience of eavesdropping that the characters feel. In a Cassavetes-like fashion, we don’t always see the entire body of the characters.1Canijo references the audition scene in The Killing of a Chinese Bookie. Both films feature long Tatiesque shots of the hotel facade with the different windows displaying their respective worlds.

Mal Viver centers on the hotel owners, and the guests are only shown in the background. In Viver Mal, the roles are reversed, with the guests playing the main roles. Here, we find Leonor Silveira and Nuno Lopes, among others. Both films are expertly acted, shot and edited. Bad Living is a strong contender for the best film of the year (I would be utterly surprised if any other film comes near). Living Bad is a remarkable work as well. Both films are not only emotionally raw but startlingly mature. Some reviewers seem to have reacted badly to this without managing to explain why. Probably, the films crept under their skin more than they care to admit.