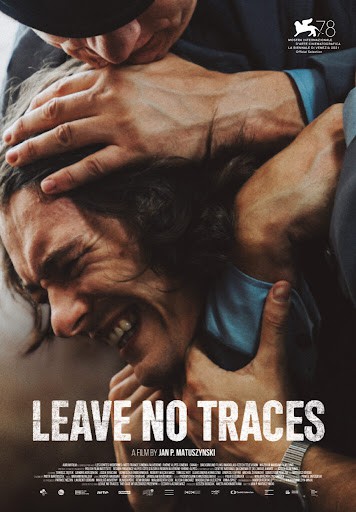

Leave No Traces (Żeby nie było śladów 2021) is the sophomore film by Jan P Matuszyński, following The Last Family (Ostatnia rodzina 2016). The topic of the film takes place a year before the director was born. In 1983, the high school student Grzegorz Przemyk is beaten to death by the police. His friend Jurek is the only witness, and he is put under intense pressure from the communist regime and has to hide from them in a safe house. The story will not merely pursue the attempts of the victim’s mother, Barbara, to achieve justice, but will focus on the elaborate cover-up by the regime as well.

Grzegorz’s death happens early in the film. He and Jurek, two students and wannabe poets, are walking in the street when some policemen appear and demand to see their IDs. When Grzegorz doesn’t comply, both are taken to a police station, where he is severely beaten. One officer instructs the other to aim for the stomach, not to leave any traces. Jurek is in the same room at the time, but his eyes are kept away from the actual beating. Later, his friend is taken to hospital, where he dies from his injuries. What follows is the relentless search for justice by the relatives. Barbara is a poet but also a political activist who has rallied with Wałęsa.

Is the treatment of her son connected to her political involvement, or is it just happenstance? Whatever the case, through inept handling by the authorities, the topic receives enormous attention, with the funeral being attended by thousands of people. Exactly how many depends on who you ask. The government allies are eager to keep the figures as low as possible. Lest anyone would think that arguments of crowd size were a new invention, here is a reminder that the fight for optics has always been prevalent in politics and elsewhere. Matuszyński’s film becomes a fascinating study, not so much on the search for truth, as in who will shape the form of truth in the general public’s eyes.

Resisting cheap puns about Leave No Traces

To witness the machinations of the government is the most interesting part of the film. To see the cogwheels at work is akin to witnessing the inevitable, horrendous logic in Miklós Jancsó.‘s works. We see general Czesław Kiszczak (Robert Więckiwicz) and the ministry official Kowalczyk (Tomasz Kot) manoeuvre the volatile space of truth and fake truth (news). At one point, one of them scolds the clumsiness that made the case big in the first place like he couldn’t believe how amateurishly it was handled. During these sections, the film feels like a conspiracy thriller from the seventies, by the likes of Pakula, Penn or even later works by Bo Widerberg. Fortunately, it never stoops to the level of Costa-Gavras.

That implies that there is never any sign of hope, which would obviously be false. It’s a film for adults who are okay with having to think for themselves without being spoonfed with sugar in the process. It’s a work that would be very difficult to finance in the US today without significant changes. It is Poland’s Oscar candidate, but I would be surprised if it goes very far in the process. The look of the film is tremendous with the 16mm cinematography and the production design working wonders to evoke the era. As a piece of cinema, it is always compelling, occasionally stunning. If it is enough to sustain the 160 minutes duration is a matter of preference.

The film is at its best when it shows the, sometimes hilarious, plottings from the government and at its weakest when it deals with Barbara. The cast is made up of well-known names. Apart from the ones already mentioned we encounter Andrzej Chyra, Jacek Braciak and in the role as a prosecutor, Aleksandra Konieczna. A very different part from the one that she played in the director’s debut feature, as Beksiński’s wife. Ziętek as Jurek is a perfect choice. The film is generally well balanced, but the use of Gorecki’s third symphony towards the end is a misstep. The film still shows Matuszyński as a promising director that will be interesting to follow in the future.