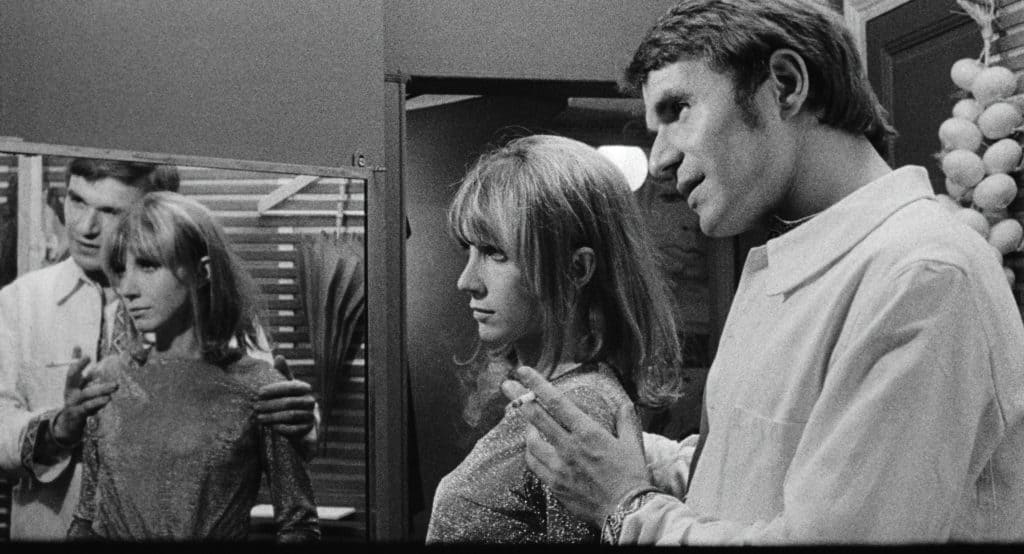

L’Amour fou (1969) is the third film by Jacques Rivette. The film was virtually impossible to watch for many years, at least in any discernible watchable fashion. It was my holy grail of cinema for decades until a festival screened it during a Rivette retrospective in 2017. It’s been digitally restored, pieced together from separate elements, since the original negative was destroyed in 1973. As in many of the director’s films, it takes place in the world of theatre. This time, a troupe is rehearsing Racine’s Andromaque. The director Sébastien (Jean-Pierre Kalfon) casts his girlfriend Claire (Bulle Ogier) in the main female role and himself as Pyrrhus. That the play will mirror “reality” in some ways is evident.

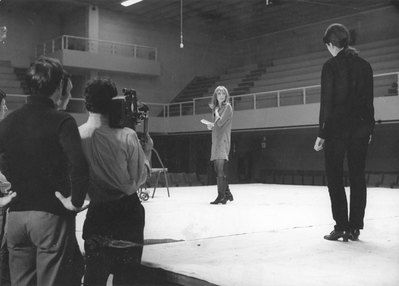

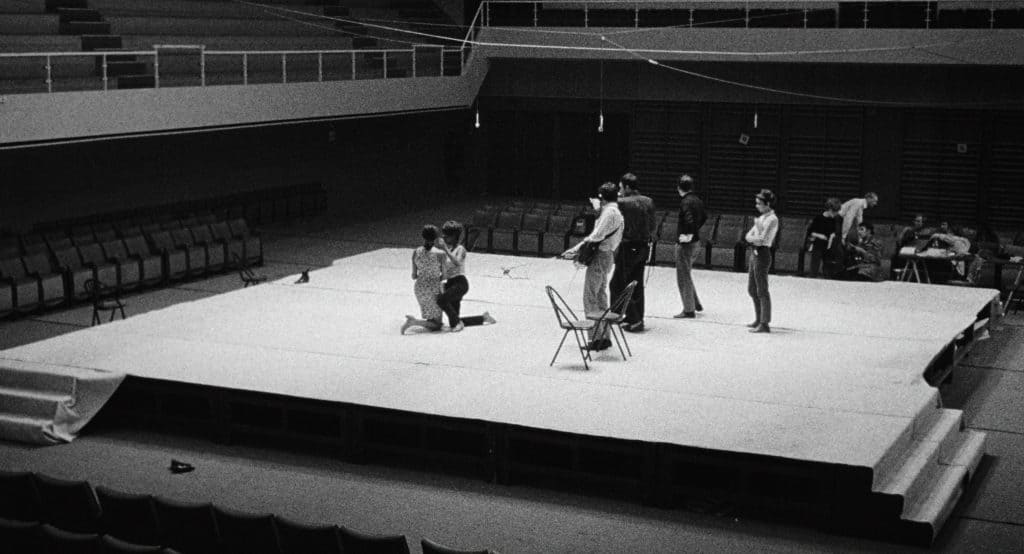

Meanwhile, a television team is filming the rehearsals, thus creating an extra layer or rather another dimension to the proceedings. The film is shot on 35 mm, but the scenes shown from the TV team’s view are lensed on 16mm. If a contemporary viewer feels fed up with all the feeble recent attempts to create such a multi-faceted mirror effect, here’s the real deal. There is not much point in going into plot developments for several reasons. They are not always clear, and the film shifts its centre(s) constantly and fluidly. Jonas Mekas wrote in his Village Voice review that he liked the film a lot but that he would have a hard time telling anyone what it was about

Jacques Rivette, at length

“The length of the play is what matters”, Sébastien says at one point. Rivette is famous for his long films, this one clocking in at 252 minutes. His longest film is Out 1: Noli me tangere (1971), with a running time approaching 13 hours. Sometimes, the director was forced to make shorter versions of his films, but almost always, they not didn’t only work worse but also felt longer than they were since the rhythm was ruined. The exception here is the shorter version of Out 1 called Spectre, which is a work in its own right.

Among the film’s many influences, the most important is the theatre director Marc’O. The two leads came from his ensemble without much film experience before. Both of them were free to shape their roles and had a considerable impact on the final result. However, the word “final” might be misleading. In many ways, the film feels like an organic object that shifts shapes while being projected. At one point, Claire violently opens a matryoshka doll, which could serve as a metaphor for the whole film, but even that would be a simplification. Mirrorings are constantly literally present, but the aforementioned structural device playfully deals with mirror effects as well. What kind of victory will Sébastien (Pyrrhus) have?

Rivette’s 35 mm shots are relatively static, whereas the TV team’s hand-held camera uses a cinéma-verité style. There is much of the latter during the first part of the film, and for someone who is not a Rivette aficionado, the first hour might be the most challenging. Once the film casts its spell on you, it will become a mindboggling experience which will attract and repel to a scintillating effect. L’Amour fou is different from the later, more Feuilladesque films by the director but nevertheless delivers a unique experience, different from others. The film was restored under the supervision of master cinematographer Caroline Champetier.

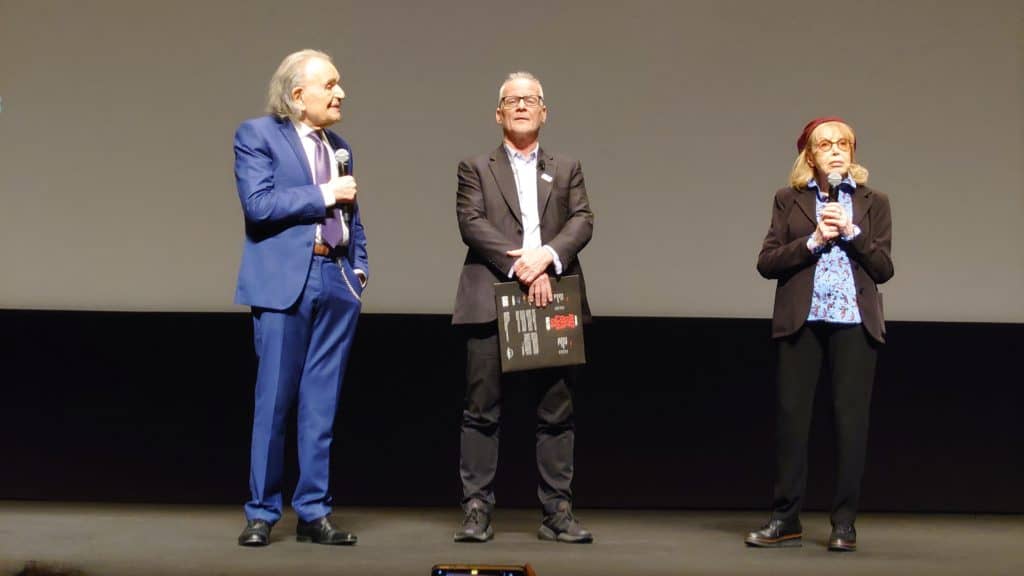

Regarding the seemingly infinite reflections of the work, watching Kalfon and Ogier on stage 56 years after the film was shot was most moving. Ogier stated that it is her favourite film of all she has done. Something that seemed to surprise even Frémaux. When the remaining audience applauded the actors afterwards, it was the most genuine standing ovation that I’ve ever seen in Cannes. I didn’t time it; I was just caught up in the moment.