The Sky The sky The earth ends and that's where the sky begins I look at it, And tonight too, it makes me think of you Il Cielo Lucio Dalla

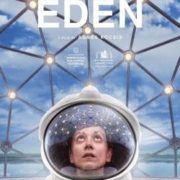

The new, eagerly awaited film by Ágnes Kocsis, Éden, premiered at last year’s IFFR. It was screened at the Gothenburg Film Festival the same week where I saw it, ten years after Pál Adrienn opened. It was already a long wait, but still not as long as the 18-year gap between Ildikó Enyedi’s two latest features. There are actually several similarities one could quote (impose?) between Éden and On Body and Soul (Teströl és Lélekröl 2017), but that is material for another text. On a superficial level, one could say that both films have male leads that are not actors: one a set designer, the other a musician, Belgian Daan Stuyven from the band Daan, which is a solo project.

Home Alone

Solo might be the operative word for the film as well. It revolves around Éva, who is sick of everything, quite literally. In the director’s words, “Éva is allergic to all kinds of chemical substances, air pollution, radio waves and electronic fields. She needs to live in total isolation and can have no contact with her environment. The slightest mistake may cause her death. Her only relations are with her brother and the doctors, continuously experimenting on her. One day, a psychiatrist comes to investigate if her illness is real or exists only in Éva’s mind.” We first see her at the clinic performing tests to react to words projected in front of her.

She is later being driven home by her brother Guyri in one of many splendid shots in the film. Éva, in a protective suit, sitting in the back seat while we see nature reflected on the car. A perfect illustration of her situation. Her access to nature and life is permanently blocked by a protection device of some kind. She has been living like this for years. The only time she goes out is to have tests done on her at the clinic. Then, one day, a psychiatrist, András, enters her life. He is hired by a corporation to prove that Éva’s condition was not caused by them. This plot device will partly occupy the first hour of the film.

However, just like the theft that seems to propel the narrative and bring the protagonists together in Enyedi’s film, the court case is primarily a MacGuffin. As Sándor Baski points out, this is not a film about allergies, viruses, or pollution but about how we can connect with each other and the outside world, both physically and spiritually. This part of the film culminates in a court scene. Afterwards, the company representative approaches András and makes clear to him that they won’t meet again. That is also the point where the film sheds this narrative crutch and solely focuses on the complex and literally cosmic subject matter at hand. Even though the case is over, András offers therapy for Éva,

Her meetings with András have already been therapeutic for Éva. Her isolation has been so tremendous that she says she has longed for the humiliating tests at the clinic since someone actually touched her skin. András seems very impressed with her as a person, even saying he never met anyone like her. Where will this lead? In a lesser director’s hands, this could easily have slipped into rom-com territory. However, András is not the Adam that will be with her in the Garden of Eden. Instead, the themes of the film will prove even more profound. There is a cosmic scale to this seemingly intimate film.

Éva is a woman of untapped potential. She seems very intelligent, being highly adept at solving puzzles and playing Memory. She is also working on a wire sculpture throughout the film. One scene that refers to Stalker (1979) might suggest that she could even have supernatural powers. She used to be a teacher and misses the children immensely. She asks to meet András’ daughter, Liza, but he refuses, saying it would be dangerous. He is protective of her as a doctor over his patient. Music, played by her neighbour, seems to have healing powers. It turns out that it is András who brings records to him to play for her. The neighbour comments that “he really likes his music”.

This might be an in-joke, referring to Daan Stuyven’s own music.1 He was cast since the film is a Belgian Co-production. Especially considering that Éva will later dance to the Daan song Swedish Designer Drugs. In a later scene, where he takes her to a Schubert concert, her feelings overwhelm her. Whether it is because of the music, the spectacular hall, or the sensation of being surrounded by so many people or all of the above is left unclear. The pandemic has, in some ways, made the film even more topical (people getting side effects from vaccine placebos during trials, for instance). More profoundly, with the physical isolation that many people had to endure and its devastating impact.

2021 – A Sky Odyssey

It’s a challenging role for Lana Baric, verging on the impossible. To quote Max von Sydow in A Passion (En Passion 1969), she has to express the lack of expression. It’s a riveting performance that commands constant attention. Not that there is a lack of other things to admire in the film. Ágnes Kocsis proves, once again, that she is one of cinema’s most supreme formalists working today. Apart from the Stalker reference, this is Kocsis’ most Kubrickian work. Not merely because Éva wears gear that looks like it could be utilized in space but for the clockwork precision of how the pieces fit into the impressive puzzle. How does the picture perform on an emotional scale?

Kubrick’s films are often described as cold and devoid of emotion. I agree with Jonathan Rosenbaum, who wrote that it is simply not true that his films lack emotion, but they are not obviously visible within the convoluted form. As I said about Pál Adrienn, there is no lack of emotion in Kocsis’ films either. There is, however, a refreshing absence of cheap shots and manipulation. The images by Máté Tóth Widamon, who also lensed the brilliant 1 (2009) by Pater Sparrow, might be the most austere in any of her films, with a feeling of modernity akin to Tati in Playtime (1967). An early scene where András is alone at the airport is particularly Tatiesque.

It is a work of tremendous beauty. The symmetry and perfection of the images match Kocsis’ immaculate conceptualization. Like the luxurious sushi that András and the corporate guy consume, this is a work made with the utmost care to detail. It is an immersive experience, even though the lack of close-ups seems to have alienated some critics. For anyone expecting a didactic work about environmentalism, the film is bound to disappoint. This is a work that is a meditation on what it is like to be a human being today, yesterday, and in the possible future. Hopefully, it will play in numerous cinemas since that is where this dense and aesthetically rigorous film belongs.

Kocsis’s next project will be a biopic about Pál Szécsi. Let’s hope there is not a Kubrickian gap until that film sees the light of day. Éden opens in cinemas in Hungary today and hopefully soon in other countries as well.