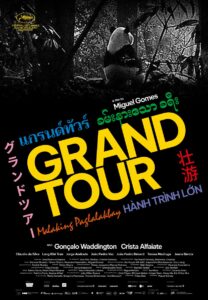

Grand Tour is the latest film by Miguel Gomes, and it premiered in the competition of this year’s Cannes Film Festival. It is his first film since the Arabian Nights Trilogy, which was screened in the Quinzaine des Réalisateurs section in 2015. Rumour has it that Gomes was unhappy with not being selected in the competition then, but I can’t believe that he was as unhappy as the spectators who made it through said trilogy. Since then, the only feature he has been involved in is The Tsugua Diaries (Diários de Otsoga 2021), co-directed with Maureen Fazendeiro. It premiered in the Quinzaine des Réalisateurs section at Cannes the same year. It’s a film that I’ve yet to watch.

Grand Tour begins in Rangoon, Burma, 1918. Edward, a civil servant for the British Empire, runs away from his fiancée Molly the day she arrives to get married. During his travels, however, panic gives way to melancholy. Contemplating the emptiness of his existence, the cowardly Edward wonders what has become of Molly. Determined to get married and amused by Edward’s move, Molly follows his trail on this Asian grand tour. That is what the synopsis says, anyway. Said tour brings Edward to Singapore, Bangkok, Saigon, Manila and Osaka. The production of the film was quite unorthodox. Gomes asked the producer to make the grand tour and then he would write the script based on the footage he would shoot there.

The producer, Filipa Reis, agreed to this unusual demand. The tour was slightly thwarted due to the pandemic, but most of it was achieved. The outcome was footage that is used in the film, occasionally boasting anachronistic elements. The narrative part of the film was largely shot in a studio without much attempt to hide the artifice. Grand Tour is a diptych, which is not surprising considering the director’s earlier output. The first part covers Edward’s flight, while the second shows Molly’s determined attempt to track him down. Like the Berlinale titles Pepe and Dahomey, Gomes’ film displays a playful relation to the narrative, not least with the voiceovers, but it feels less profound than either of those two works.

Is this really a Grand Tour?

The film credits three cinematographers: the Portuguese master Rui Poças, Gui Liang, and Sayombhu Mukdeeprom. Ostensibly, Poças was responsible for the studio material, which is visually appealing. Still, one might feel that there is less to this than meets the eye. Even though I appreciate and even admire aspects of Gomes’ work, I often felt that something was missing without being able to pinpoint exactly what it was. That was the case already with his first hybrid feature, Our Beloved Month of August (Aquele Querido Mês de Agosto 2008). Even with Tabu (2012), which is arguably his most accomplished work to date, I had the same sentiments, and I’ve never rewatched it.

The same goes for Grand Tour. The film won the director’s award at Cannes, which was well deserved in a competition where few films were even watchable. Still, the reactions were mixed. Some critics were utterly delighted, while others were bored or annoyed. I ended up feeling both ways during different parts of the film. Cinema is an art form that relies on the collective, where some directors have achieved fame simply by choosing the right collaborators (Wajda is a prime example). I wouldn’t go that far with Miguel Gomes, but Grand Tour wouldn’t be as successful as it is without the cinematographers who are on board.

In any case, it is a film to recommend, but it is quite far from a grand film.

Grand Tour

Director: Miguel Gomes

Date Created: 2025-09-18 16:57

2.98

Pros

- Cinematography and its diversity

- Intriguing tyle

Cons

- A bit too fond of its own ideas.