Fotográfia (1973) is the most famous film by Pál Zolnay, even though it is somewhat forgotten nowadays. The film begins in Budapest on New Year’s Eve. While people are celebrating, several photographers walk around taking pictures that they offer to sell later to their subjects. The sequence is shot in a manner that oscillates between documentary and fiction. Sometimes people look straight into the camera; at other times, the lens focuses on an individual that will turn out to be the protagonist. He turns out to be in the same trade himself, and it seems that what he experiences on this night gives him a business idea.

With a friend who is a retoucher, he will go around the Hungarian countryside, photograph people in villages, and offer to sell their photos to them. They go from village to village only to find that people have varied views on being photographed. One thing they seem to have in common is that they are not interested in the “real” pictures, which they deem ugly, but ask for retouching. Zolnay’s initial idea was that the film would be centred around this dichotomy, and there would be a certain tension between the two protagonists. There was no script but merely some situations where the themes were supposed to be depicted. Then something happened that changed the course of the film.

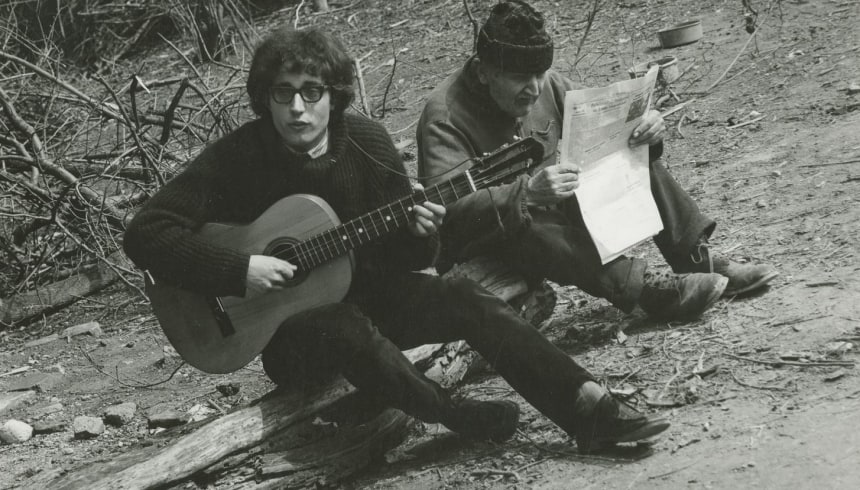

Suddenly, a person tells the story of a double murder of two young sisters that occurred years ago. The people involved are still around in the village, but some don’t seem eager to talk about it. This unexpected and shocking story had a profound impact on where Fotográfia would put its focus. Still, it never resorts to becoming a simple murder story, either. The dynamics of the film are difficult to put into words, but it seems to be constantly changing organically. There is a musician following our main characters singing songs that may or may not reflect the action in the film.

The look of Fotográfia

Fotográfia never makes clichéd statements about reality vs fiction but handles the themes deftly. If I should make any reference to another filmmaker, Kiarostami comes to mind, especially the films made after the Koker trilogy. Zolnay manages to find a unique film language that doesn’t fall into either the fiction or documentary category but, at the same time, comments on both. If that is not enough, the film is shot by the master Elemér Ragályi and is consistently a joy to behold. The film packs its short running time with beautiful images and plenty of food for thought. Anyone being seduced by a movie like Visages Villages (2017) for some reason will find much more substance in Zolnay’s work.

The film is available on Filmio for a small fee with English subtitles. It comes highly recommended.