Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.

Whereof can be spoken at all, thereof must be said clearly, or fuckin’ screamed out loud. Right?

Róbert Frank

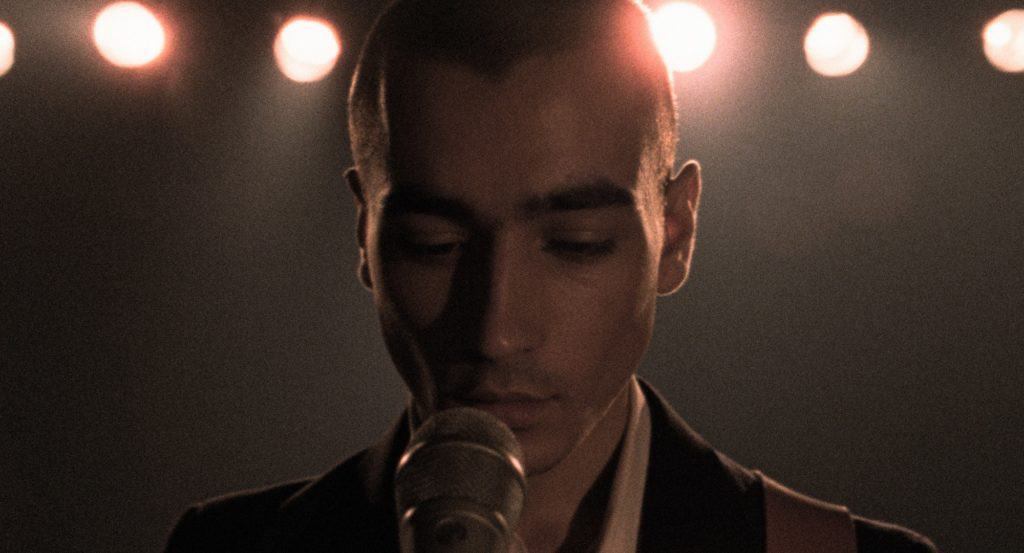

These are the words of the protagonist in Erasing Frank (Eltörölni Frankot 2021), the first feature by Gábor Fabricius. Set in 1983. It follows the charismatic frontman of a banned punk band. His anger at society is expressed in his music. He is arrested by the police and sent to an open psychiatry ward. He enjoys relative freedom (“relative” being the operative word). He meets Hanna (Kincsö Blénesi), who becomes his main ally. Another encounter is with the cultural leader Erös (István Lénárt in his final role), who becomes an ominous but frail presence as a representative of the state. The film opened at Venice International Film Critics’ Week, where Gàbor Fabricius won the Circolo del Cinema di Verona Award.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that the film stands and falls with Benjamin Fuchs’ performance. He is virtually constantly visible. Chosen among 1500 people, Fuchs delivers a strong performance and is one of the films’ major assets. His scenes opposite Lénárt’s aged state bureaucrat are particularly telling. Erös (strong) is an ironic name since he actually looks extremely frail. István Lénárt died in 2021, one week before what would have been his hundredth birthday. His portrayal here is indicative of a system whose former strength is falling apart.

The true colours of Erasing Frank

The cinematography by Tamás Dobos (Perpetuity, Natural Light) employs a handheld camera, which gives the film a documentary feel, according to the director, influenced by the Budapest school. It was a movement that sprang out of the Béla Balázs Studios. Those works were often in black & white. An odd thing with Erasing Frank is that it was screened in colour in Hungary but in black & white abroad. The film seems to have met more enthusiasm outside Hungary, where many critics pointed out the similarities with Hungarian society today. The topic of liberty is obviously not a new one. The “relative freedom” of the psychiatry institution brings to mind the discussions on the subject in István Gaal’s classic The Falcons.

It could be questioned how original the whole affair is. It has several similarities with other works on the same topic. Compared to a recent film like Leave No Traces (also set in 1983) with its methodical illustration of how the power system works, Fabricius’ film feels slight. On a technical level, it’s a highly accomplished piece of filmmaking with Dobos’ kinetic lensing, Wanda Kiss’ editing, and the masterly sound design. Still, it’s more impressionistic than anything else and doesn’t leave much to ponder once the film is over.