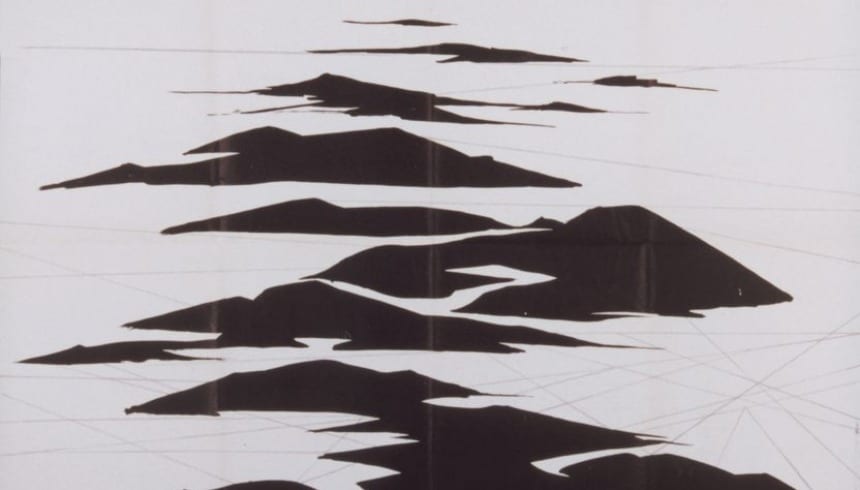

Cold Days (Hideg napok 1966) is the most famous film by András Kovács. It belongs to the classics of Hungarian cinema that were named the twelve best Hungarian films by the Budapest 12 critics. The film is set during WWll, specifically the 1942 massacre in Novi Sad (Újvidék in Hungarian) against more than 3000 Serbians and Jews, administered by the Hungarian army. The film begins with an explosion on the ice of the river Duna, accompanied by Béla Bártok’s Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta (14 years before Kubrick utilised the same third movement in The Shining). A narrator recounts the massacre and its legal aftermath. He explains that the events themselves are not the topic of the film.

Kovács’ film is set in 1946 and focuses on four imprisoned officers who reminisce about those days from different perspectives. They are accused of participating in the events, and their respective memories give the film its structure. They sometimes talk about different circumstances and, at other times, the same ones, but from different angles. Based on the eponymous novel by Tibor Cseres, the film examines a part of history that wasn’t much talked about before and even less portrayed in fiction. There was a tendency to focus on victorious events, such as in Egri csiallagok, which was filmed in 1968 in colour. It was shot by Ferenc Szécsényi, who also lensed Cold Days, but the films couldn’t be more different.

Cold Days on the plain

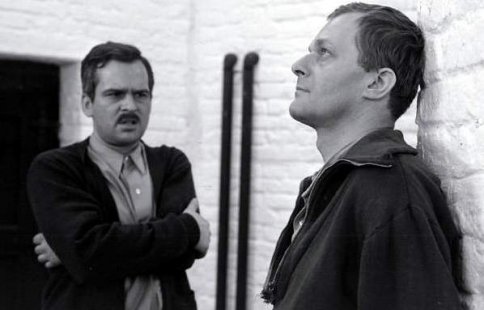

Whereas Egri csillagok tells the story where Hungary enjoyed one of the country’s few victorious historical moments in bright colours, Cold Days was shot in B&W and depicts a literally ice-cold reality. The scenes from the prison with its whitewashed walls have an intense feeling that might bring Jancsó‘s The Roundup (Szegénylegények) to mind. The films were released the same year, and both directors were influenced by Antonioni, which is evident from a late foggy scene. The setup with some men in a prison cell awaiting their fate might bring the aforementioned Kubrick’s Paths of Glory to mind. Still, Kovács’ film has none of the infuriating sentimentality of that early Kubrick work. The acting is uniformly excellent.

András Kovács studied psychology, sociology and aesthetics before his film studies. All those elements come together expertly in the finished work. The blocking in the prison sequences could warrant a study in itself. Even in a cramped cell, the distance between the characters is accentuated in the framing, as well as the way they regard each other. The philosophizing in the dialogue is akin to the films of Zoltán Fábri but adds a more keen visual sense, where the dialogue never unbalances the film. The didacticism is also kept in order, with no facile moralism. There are no heroes here, for sure, but possibly the bad guys are not so easy to point out, either.

Kovács would continue to make films such as Falak (1968) and The Stud Farm (A ménesgazda 1978), both of which are interesting, as well. The latter was restored and re-released recently. Still, Hideg Napok remains the work that puts his name in cinematic history. It won rave reviews upon release and received a critics’ prize in Karlovy Vary, as well. The film is available in a beautifully restored version on Vimeo with English subtitles. It is highly recommended, not least for those who have seen similar later films that didn’t hit it out of the Park. Incidentally, the director’s son is András Bálint Kovács, the distinguished film scholar who has written several books, including one about Béla Tarr.