Disclaimer: I regurgitated all my eating metaphors before writing this text.

Club Zero is Jessica Hausner’s sixth film and her second in English. Six films in 24 years don’t make her the most prolific director, but for some time, she’s been one of cinema’s strongest formalists, next to Ágnes Kocsis and Lucrecia Martel. With her previous film, Little Joe, she started making films in English. I was not overly impressed by that film even after watching it twice in a cinema. The new offering is in English, as well. It opened in the Cannes competition on the same day as Kaurismäki’s Fallen Leaves, but the critic’s reactions to the films couldn’t have been more different. It was actually only the second time Hausner had a film in the Cannes competition.

Club Zero commences with a warning. It’s not entirely clear whether it’s serious or ironic. Trigger warnings generally do more harm than good and have become so ubiquitous that they are practically useless. Whether it was demanded by the producer or not, it still comes off as satirical. We’ll get back to irony later. The story is set in an elite boarding school where the recently appointed nutrition teacher, Ms. Novak (Mia Wasikowska), waltzes in with unorthodox ideas that will appeal to some pupils. Initially, those theories involve “conscious eating”, but they will go way further down the line to end up in the titular club. She is basically approved by the principal since she is willing to work weekends.

What is the purpose of Club Zero?

The script is written by the director and her regular partner in crime, Géraldine Bajard. Many critics seem to regard the film as a satire and have expressed disappointment in not finding the target of said satire. The press conference in Cannes was also a strange affair where some questions were about pesticides in food. So, what is Club Zero about if films have to be “about something”? The ambiguity of the opening trigger warning may carry over to the film in general. The film the director talks about in the press kit bears only a slight resemblance to the one that premiered at Cannes. The hostility from the Anglo-Saxon critics seems incomprehensible and comical at the same time.

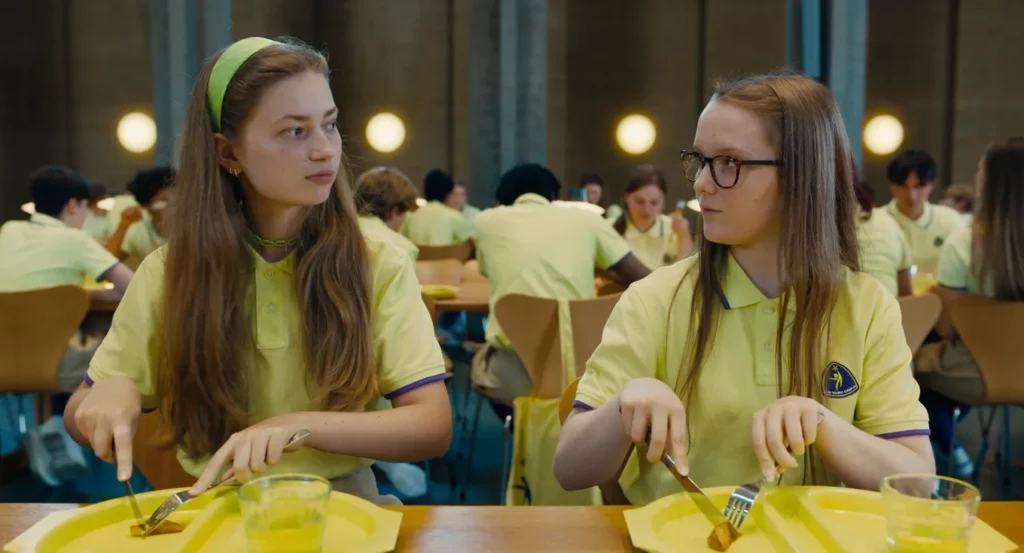

The environment is always a crucial element in Hausner’s work. Here, she utilises St Catherine’s College, which was built by Danish architect Arne Jacobsen. His modernist style caused quite a stir when he was appointed to design the Oxford college. Hausner chose the location to deviate from the typical British style. Likewise, the costume designer, Tanya Hausner, decided not to have the pupils wear typically English college garb but something quite different, and as she phrased it, “A unisex uniform which I think is very nice”. This is merely one of the points where the purported aim of the creators clashes with the outcome of the finished work, at least the way I see it.

In several ways, Club Zero is a perfect representation of today’s society. As I alluded to in my review of Without Air, parents have far too much influence over schools today in place of the professionals working there. Students and their parents have become customers making demands on the school rather than the other way around. This is spelled out by the principal, Miss Dorset (A marvellous Sidse Babett Knudsen), when she meets Ms Novak. “All our children are highly talented. At least, that is what their parents think. And it is our task to meet the parents’ expectations.” Then, she asks about the aforementioned weekends, which Ms Novak is happy to cover since she is single without children.

In the very first scene, Ms Novak rounds up seven pupils who will explain why they are attracted to conscious eating. Their reasoning is a token superstructure built to cover their own narcissism. One wants to protect the environment; another wants to achieve self-control; a third person wishes to reduce her body fat, while the least wealthy one, Ben wants to increase his scores for a PhD scholarship. Ms Novak assures them that all of their individual goals will be accomplished by conscious eating. Lo and behold, how lucky the kids are to run into her. An additional irony is that Ms Novak is not a strong, seductive character but comes off as a sad and lonely one.

That Ms Novak encouraging the children not to eat endangers their health doesn’t seem to be a big deal. When she gets ousted from her position, it is for taking a pupil to the opera. Even though it’s done in public, that violation is deemed more unacceptable. Almost exactly at the one-hour mark, a member of Club Zero says that it feels like she is part of a revolutionary movement. Ben answers “Me too, me too”. Again, it’s not certain that it is an intended irony on the writers’ part. Still, what the film captures with the utmost precision is the current herd mentality that can break out at any time, for instance through social media, and ruin peoples’ lives.

The world today is full of “movements” that ostensibly started with the best intentions, to quote a compatriot but have transformed into ruthless power machines, whether it is BLM, #MeToo, transgenderism, environmentalism or whatnot. Meanwhile, proper science is shunned in lieu of how people “feel.” Universities and other pedagogical institutions, which once were counterparts to that tendency, now seem all too eager to follow their students’ whims. Club Zero displays idealism in its crudest form, and the reason it can go on is that people have their own petty issues. When Miss Dorset meets Ms Novak after her dismissal, she laments the fact that nobody will be able to work the weekends anymore instead of worrying about the big picture.

Hausner presents a dystopian world devoid of sensual pleasures. Boys and girls look and dress the same, and there doesn’t seem to be much attraction between them. Early in the film, there is an inept attempt by Ben to get a girl’s attention, which she rightly finds merely weird. The exception is the colourfully dressed Miss Dorset, who seems hungry for life. In a hilarious scene, she eats in front of Ms Novak, who comments that “it’s normal”. It is indeed, but she means it sarcastically, feeling superior in her purity. Why the film was received with hostility at Cannes is anybody’s guess. Maybe the initial trigger warning was meant for the critics.

Upon leaving the screening, I had a similar feeling to the year before after reading some reactions on Triangle of Sadness. Critics accusing Hausner of being cynical might actually have felt that the themes of Club Zero hit too close to home. A compatriot of mine called the film weak, which is a reasonable view, but reviews that accused the director of attacking teachers and juxtaposing her with Republican politicians in the US clearly were personally provoked.

When it comes to the film’s cinematic qualities, I’m torn. Hausner’s and cinematographer Martin Gschlacht’s style is easily recognisable, but there was more than one instance where I felt the film came off as Hausneresque, repeating former stylistic traits. For the second time, non-diegetic music is used. The composer, Markus Binder, explained that the director asked for something irritating, referring to an extra layer of distancing. Personally, I think the music works better in this film than in its predecessor.

Still, both films are in English, which is clearly a detriment to them. Some critics were quick to point out the erroneous choice of words in key scenes, but more serious is that Hausner clearly doesn’t understand the effect of certain intonations. There is a new project being prepared about workplace culture, with the working title Toxic. When she presented the project in Sarajevo last year, it wasn’t decided if it would be in English or German. One can only hope for the latter.