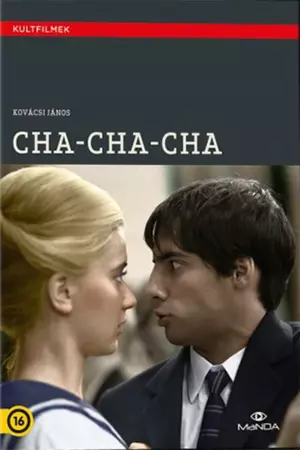

János Kovácsi didn’t make many films and is primarily known for his debut, Cha-Cha-Cha (1982). Ernö (Péter Rudolf) is a typical 16-year-old growing up in Budapest in 1962. In the very first scene, we see him standing in a line outside, waiting to buy a big chunk of ice. The sequence is largely shot from above, which emphasizes the emptiness of the square and effectively paints a gloomy picture of life back then. He carries the block home and tries to fit it in the fridge since it’s too big. His irritated attempts to chop the ice are quite tragicomical. Etnö lives with his big family in a large flat with a hall in the center of the action.

Early in the film, Ernö’s friends manage to get some girls to the flat. This means that he will have to lock his grandmother in her room. Her screams are still audible while the guests are present. It is soon evident that he is much less adept at dealing with them than the other boys. The Sunday afternoon dance classes are supposed to remedy that condition and meanwhile teach the youngsters how to dance, whether it is the titular cha-cha or something else. The dance instructor and his assistant are highly enthusiastic, while the other participants seem to have other things on their minds. The lessons teach strict rules for dancing down to the smallest hand gesture.

The structure of Cha-cha-cha

Ernö’s partner, Fanni (Enikö Eszenyi), suffers from sweaty hands, which becomes a discussion topic while dancing. At the same time, he is daydreaming about the seductive Fekete Virág (Rita Tallós), 1Literally meaning Black Flower, fantasizing about being her saviour. When the drummer stops playing in the middle of a song to start drinking alcohol instead, one could start to wonder if there is a risk that the film will fall down the cheap comedy hole. Still, it will instead focus on the structure (or lack thereof) of the dancing in a scene that bears some resemblance to the beginning of Friss Levegö, albeit not on the same formal level. The film will successively turn bleaker until it’s not even bittersweet.

Janós Kovácsi would later move to the US and be more known as a writer than a director. Cha-cha-cha is his most famous work by far. Set roughly in the same era as Gothár’s masterful Time Stands Still (Megall az idö), it never reaches that level, and it was slightly surprising when the film was digitally restored in 2011. Still, the film holds many pleasures, such as the acting of thespians who would become more famous later on. The restoration brings out the best of Nyika Jancsó’s nuanced cinematography. (The use of the hall is particularly inspired) He is credited as Miklós ifjuság Jancso, literally meaning young Miklós Jancsó. Another of Jancsó’s sons, Dávid, is an editor.

One could point to political references. They are virtually unavoidable, but it is far from the film’s primary aim, and one can easily enjoy the movie without focusing on such matters. It remains a fresh contribution to depicting the youth in Hungarian cinema.