Tarik Saleh, the director behind Boy From Heaven (Walad min al janna), became known to the Swedish audience with the news magazine broadcast Elbyl in the late nineties. Later, he made documentaries with Erik Gandini, such as Sacrificio (2001) and Gitmo – The New Rules of War (2006), about the Guantanamo base during the Iraq war. In 2009, he presented the animated Metrotopia, which won several awards. However, his most well-known film is The Nile Hilton Incident (2017), about the murder of the Lebanese singer Suzanne Tamim. Since then, Saleh has been banned in Egypt, which explains why Boy From Heaven was shot in Turkey, even though the supposedly dramatic and elusive story is set in the Muslim world of Cairo.

Adam, the son of a fisherman, is offered the ultimate privilege to study at the Al-Azhar University in Cairo, the epicentre of the power of Sunni Islam. Shortly after his arrival in Cairo, the university’s highest-ranking religious leader, the Grand Imam, suddenly dies. Adam soon becomes a pawn in a ruthless power struggle between Egypt’s religious and political elite. That is how the synopsis reads, which is usually the barebone description of the film. In this case, it literally is the film. Literally being the operative word here, all the film’s qualities are embedded in the script. The instructions to the cinematographer, Pierre Aim, seem to have been reduced to “keep the sharp angle”, on which he obliged.

The absence of style in Boy From Heaven

The storyline seems to be inspired (in want of a better term, since there is little inspiration here) by political thrillers of the seventies. Still, it’s devoid of any of the cinematic qualities of The Parallax View (1974) or All the President’s Men (1976). Even David Fincher feels compelling in comparison. It is virtually impossible to describe how cinematically bland the film is, but anyone who has seen a Netflix thriller hungover at 4 PM on a Sunday afternoon should be able to imagine how drab Boy From Heaven feels. Blown up on the big screen of Grand Théatre Lumière, the effect is severely amplified and conspicuous. The scattered attempts at emulating Hitchcock merely heighten that effect.

How it ended up in the Cannes competition should be a mystery, but considering other films that made it there, it actually makes sense. Considering that the script is seemingly the only part of the film the filmmakers seemed to be interested in, the award for the best script should make sense, right? Sadly, the answer is no. The scenario is the most talkative imaginable, where even Christopher Nolan might step in and tell the people involved to ease up on the exposition. It was far from the only film lacking cinematic flair, but considering the splendid locations involved, one could have expected more. To add fuel to the fire, the film is also overlong.

Clocking in at 126 minutes, with a story that could have been told in half an hour, the boredom quickly sets in. When Another Country won an award for cinematography at the 1984 Cannes Festival, a French critic blurted out that the film was made by a Téléast. In the age of Netflix, that might not work as a slur anymore, but the lack of attention to the cinematic aspects made several films in the competition a chore to get through this year. Skolimowski and Serebrennikov were the obvious exceptions, with the latter not even receiving an award. The jury’s conclusions are rarely anything to take seriously, but this year, the decisions felt random even by festival standards.

Three years later, Saleh would return to Cannes with Eagles of the Republic. It turned out to be merely marginally less inept than Boy From Heaven.

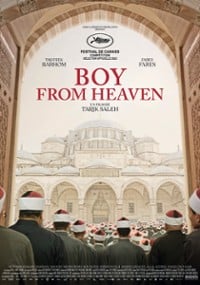

Boy From Heaven

Director: Tarik Saleh

Date Created: 2025-07-13 04:57

1.5

Pros

- None

Cons

- Dialogue

- Lack of compelling cinematography