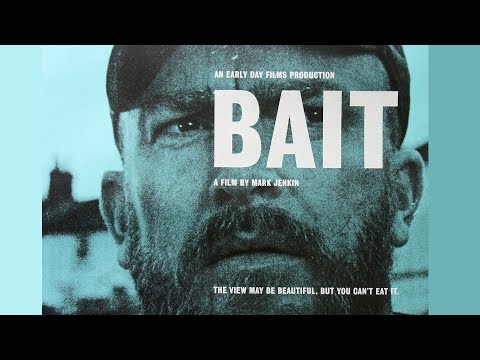

Mark Jenkin is an unusual director in this digital age. To begin with, he has a cutting room, and that room has a floor. However, he doesn’t leave anything on the cutting room floor. That is one of the things we learned during the Q&A of his film Bait when it had its world premiere at the Berlinale Forum. It is shot on 16 mm, incidentally not the first feature I saw in that format during the festival. Denis Coté’s competition entry, Répertoire des Villes Disparues (Ghost Town Anthology), was also shot on 16 mm (one of my favourite films in the competition.) Bait, however, turned out to be the standout of all the entries I saw during the week.

Bait is set in a fishing village in Cornwall. Martin is a fisherman whose life has been overturned by the tourism trade. He has been forced to sell the cottage where he was raised to a London couple. His brother Steven, on the other hand, has embraced the new reality and has started to use the former family fishing boat to take semi-drunk tourists on cruises. Martin, who is intent on making his livelihood on fishing, catches whatever he can and is set to save money to get his own boat.

There is an obvious theme of old vs new, city vs countryside, and the film is highly topical in these Airbnb times. If one is so inclined, one might add analogue vs digital to the mix. It’s worth noting, though, that the film doesn’t get overly didactic. Even though we might sympathize with Martin, does it mean we have to resent his brother for adapting to the new circumstances? And while the Londoners may not come off as the most sensible people, Jenkin is still far from the simplistic moralizing that the tale might have slipped into.

Mark Jenkin

We’re working in an art form that is 120 years old, and we already seem to have given up on the discussion of what the form should be.

If the characters are not black and white, the cinematography certainly is, with strong contrasts. Bait is not only shot on 16 mm but also hand-processed, which obviously lends a vintage feel to the project. Still, it feels more archaic than nostalgic. Critics have mentioned Russian cinema and Kuleshovian montage. I guess it’s a veritable Rorschach test, which directors come to mind while watching the film. I clearly understand the Eisenstein references and also to Vertov’s The Man with the Movie Camera (in particular, the contrast between work and leisure.)

Bait French Manicure

To me, though, the most obvious reference is Jean Epstein. Partly because his films occasionally used the sea as a location (La Tempestaire (1947), for instance) but most of all because of the cinematic means employed. Not merely his use of close-ups but also the editing, including the use of flash-forwards. In Bait, a flash-forward, including handcuffs, is particularly memorable. I also thought of Marcel L’Herbier and his use of montage in L’Argent (1928). Whether that says more about me than about the film is an open question. In any case, the film is much more than the sum of its cinematic lineage.

British Handcraft

It is refreshing with a director who is clearly interested in the formal aspects of cinema and who is not afraid to make bold choices. At the Berlinale Q&A, Jenkin lamented the lack of experimentation in contemporary cinema. Something that was all too visible in this year’s rather lacklustre edition of the festival. It was a long time ago that I saw a film where every frame felt so purely cinematic.

With the jarring editing and extensive use of close-ups, the grainy visual texture of the film felt like a breath of fresh air in a rather disappointing selection. At the risk of overlooking what Jenkin wants to say about class, power and gentrification, to me, Bait is, first and foremost, a love letter to cinema, and it’s clearly handwritten.

An interview with Mark Jenkin

Pingback: Martha Stephens interview about the captivating To the Stars