Adoption

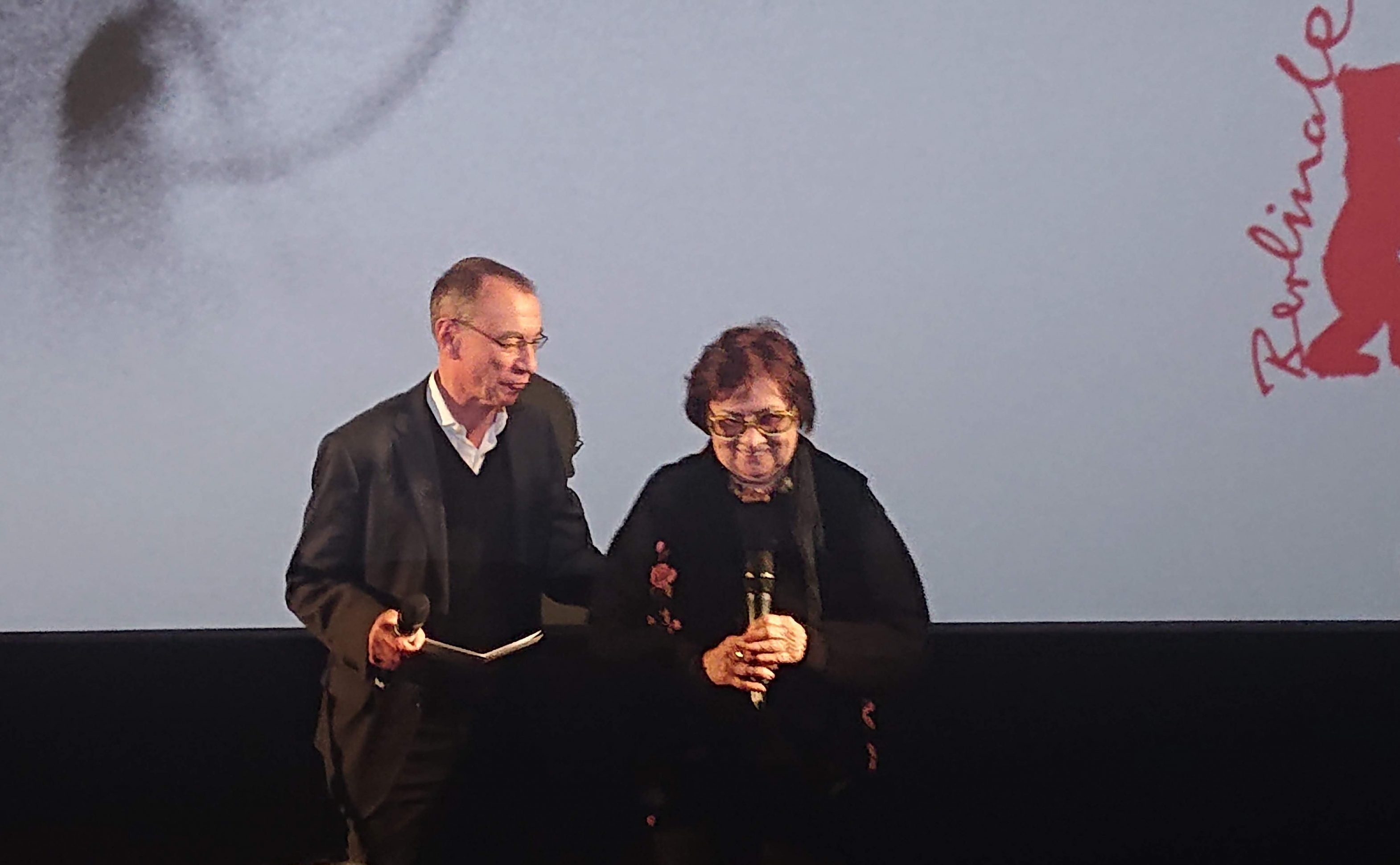

“Never adopt a child. Abandoned children are all wounded.” The quote sounds like it could be lifted from Systemsprenger but is actually from Adoption (Örökbefogadás 1975). The line is spoken by Anna, a girl from a boarding school to Kata, who is considering adopting. Mészáros’ film was the first Hungarian film to compete in Berlin, and she won The Golden Bear in 1975, as well as a bunch of other awards, which made her the first woman ever to walk away with the main prize of the Berlinale. In 2019, a restored version of the film was screened in Berlinale classics, with Mészáros in attendance.

Kata (Katalin Berek) is a 43-year-old factory worker who lives alone. The film starts almost like a British Sink realism film. We see Kata wake up, take a shower and make breakfast. Then, we follow her when she goes to work, where we also see her perform her monotonous tasks.

She has a lover, Jóska (Godard regular László Szabó). She wants a child with him, but he rejects the idea. When she later meets Anna, the idea of adoption comes to her. Anna moves in with Kata to be able to meet her boyfriend, Sanyi, and an unexpected friendship begins.

The director co-wrote the script with frequent Jancsó collaborators Gyula Hernádi and Ferenc Grunwalsky. It paints a bleak portrait of Hungary in the mid-seventies, notably for women. This fact is demonstrated in scenes that are uncomfortable to watch but still quite understated. Mészáros, thankfully, never becomes overly didactic even though the film can clearly be labelled as a feminist work. What stands out the most is maybe the frank and unsentimental depiction of a woman’s situation in Hungary’s seventies. The style is unfussy but focused and gives the actors plenty of space to shine.

Márta Mészáros may not be one of Hungarian cinema’s most inventive stylists, but there still are moments of cinematic ingenuity. For instance, in the meeting between Kata and Jóska, discussing the child. The scene starts with them sitting at a table outdoors with the camera slowly circling around them, mirroring the calm discussion they are having. Then, the scene continues inside (since Kata says she’s cold). This time, the discussion gets slightly more heated, depicted by cross-cutting.

The restoration was performed under the supervision of the cinematographer, Lajos Koltai. He would later work for directors like Péter Gothar (Megáll az idö 1982) and Pál Gábor (Angi Vera 1979), but maybe he is best known for his work with István Szábo, in particular, the Klaus Maria Brandauer trilogy: Mephisto, Oberst Redl and Hanussen. The film holds up well after 44 years. Even though Mészáros may not rank among the top tier of Hungarian filmmakers, the film is worth seeing for its honesty alone.

Adoption by Márta Mészáros - The Disapproving Swede 1975 Powerful

Director: Márta Mészáros

3

Pros

- Honesty

- Acting

- Lajos Koltai

Cons

- The style is not groundbreaking.

Interesting comments on a fine film. The restoration had a different aspect ratio from the original release; the pre-screening interview commented on this. I wondered if you had any thoughts on this?

Hello Keith,

That’s an interesting question. The trailer, posted by The Hungarian Film institute just before the 2019 Berlinale, was in 1.66:1. I always thought that was the OAR. That was also the ratio of Malavida’s release in France. In the US, however, Kino released a version in 1.33:1. I’m certainly no expert on this film, and I’m not sure which is the correct one. Then, there is the issue with restored films being released on 16:9 Dvd and blu-ray, which is closer to 1.77:1. Sometimes a “director approved” release actually has a different OAR than the original release. One such example is Jancsó’s Red Psalm. It was originally in the Academy ratio but was released in the UK in 1.77:1. Meanwhile, Clavis in France released the 1.33.1 version.

Chris