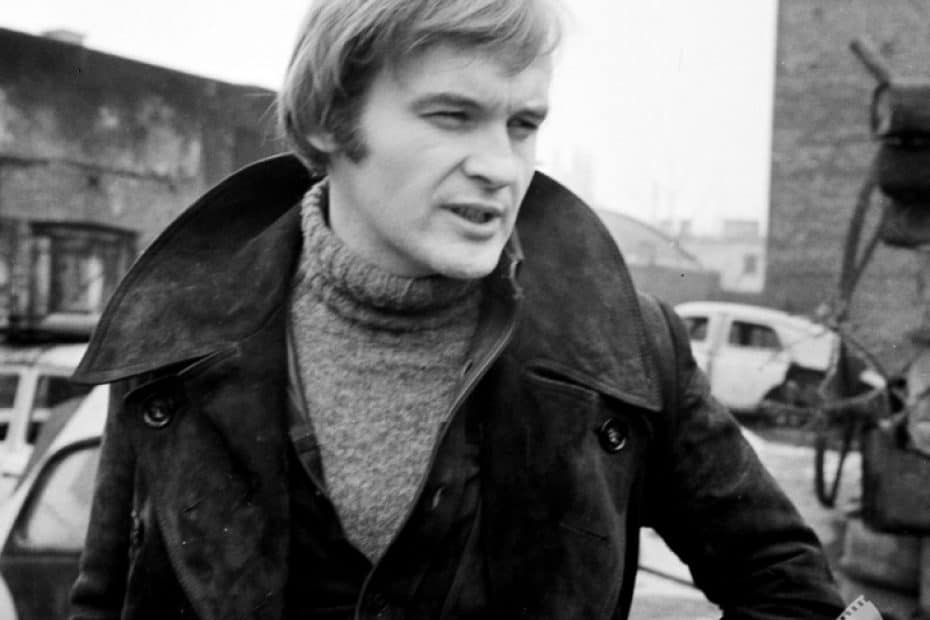

Jerzy Skolimowski is one of the most prominent Polish directors and a personal favourite of mine. Born in 1938, his first credit was as a screenwriter in Andrzej Wajda’s Innocent Sorcerers (Niewinni czarodzieje 1960). Two years later, he co-wrote Roman Polański’s debut feature, Knife In the Water (Nóż w wodzie). Both films were unpopular with the Polish government at the time and were deemed anti-social and containing bad role models for the Polish youth. The title of Wajda’s film, which was very atypical for the director, came from Adam Mickiewicz’s classic Dziady. A play that I once saw performed at a Polish theatre in contemporary style, directed by Radosław Rychcik.

Skolimowski’s first feature was his graduation film Identification Marks: None (Rysopis1964). It was followed in quick succession by Walkover (1965) and Bariera (1966). They were all conceived as metaphors for a dehumanized society where confrontations were constantly present. In Walkover, the parable was conveyed through boxing, which was a sport that the director himself was active in at the time. Like in Knife in the Water, the confrontations revolved around two generations with different attitudes. It wasn’t the case that Skolimowski, in a simplistic fashion, sided with the young ones even though their rebellious attitude was closer to him. His films displayed the tension between breaking the barriers or adapting to the ruleset.

There was a New Wave freshness to the director’s films but with higher stakes because of the political climate. This fact would become evident in his next project, Hands Up! (Ręce do góry), which was censored by the state and only released in its intended form many years later. The experience led Skolimowski to start making films abroad. Le Départ starred Jean-Pierre Léaud as a man obsessed with racing cars. Yet another character with a feel for his automobile, and it wasn’t merely Léaud’s presence that made the film seem reminiscent of the French New Wave, but the style and sense of joie de vivre as well.

1970 saw the release of Deep End in England, and it remains one of the peaks of the director’s output. It was his second film in colour (the first is best forgotten), and the lensing was only one of the numerous strengths in the disturbing tale about a 15-year-old boy that becomes obsessed with a swimming bath attendant. Thanks to BFI, the film can now be enjoyed in a glorious restored fashion. In 1982, Moonlighting became a critical success with Jeremy Irons in the story about Polish contract workers in England during the military takeover in Poland. Skolimowski would make some more films until 1991 when he decided to stop directing and devote his time to painting.

The Return of Skolimowski

The gap would last for seventeen years. In 2008 he returned with Four Nights With Anna (Cztery noce z Anną), which screened in Un Certain Regard in Cannes. I vividly recall the excitement of seeing a new film by the director after such a long hiatus. The movie lived up to the expectations. A crematorium worker is in love with Anna and spends four nights with her, but not how you would expect. Excellently acted and with perfect lensing, the film was a triumphal return and won Polish awards for direction and cinematography. Four Nights With Anna also boasts a rape scene that is truly horrific and emphasizes the violence of the act.

The Venice Film Festival was the venue for the next Skolimowski premiere. Essential Killing walked home with three awards from the 2010 edition of the festival, one for Vincent Gallo in the virtually mute central role. His portrayal of the Afghan POW escaping capture from the American military is a gutsy one, typical of the actor. The film is nearly devoid of dialogue, except for some small talk between the Americans and later some lines in Polish. The director has called it his best film to date while simultaneously calling his first colour film the worst. It’s a visceral experience and a unique and strong one.

11 Minutes is his latest feature to date, released in 2015. It is, quite simply, a depiction of several people in Warsaw whose lives intersect during the titular minutes. It won a Special mention in Venice, but in many ways, it is one of the director’s most puzzling films, not only because of the literal jigsaw of the plot. An actress is in a meeting with an American producer who obviously wants to Harvey her before she gets a part. Meanwhile, her jealous husband is roaming the hotel. Several other characters are intertwined in a film that, towards the end, has a sequence that could work as a calling card for an American career.

Then there is a final shot that suggests a different film altogether about perception. 11 Minutes is a film that I’m not sure about its intentions and might require more than the two viewings that I have given it so far. Skolimowski will be back in the Cannes competition this year with a film called E O, representing the sound that a donkey makes. It seems to be a variation of Bresson’s Au hasard Balthazar (1966), which was one of several French-Swedish co-productions at the time.

I can’t wait to see what the Polish director will make of the Balthazar multiverse. Did his acting part in The Avengers (2012) inspire him to delve into the Bressonian metaverse? Only time will tell.

Innocent Sorcerers: so .. nice movie! 🙂