A Játszma was penned by Norbert Köbli, a screenwriter born in 1977 who has been involved in several successful projects in recent Hungarian cinema. After serving as a script doctor on some rom-coms, he adapted the stage play for Gergely Fonyó’s highly popular Made in Hungaria. (2009). A more artistically rewarding work followed in 2010 with Áron Matyassy’s Tanár Úr Kérem, which was a depiction of Frigyes Karinthy’s classic book A Journey Round My Skull, about his brain surgery in Sweden. The subsequent year brought out A vizsga (The Exam), directed by Péter Bergendy, a tight thriller set in 1957, which examined tactics used by the communists at the time.

I attended a screening of A vizsga, where the director expressed his scorn for highbrow cinema and claimed that the path forward was to make films that “people actually want to watch.” Regardless of how cringe-worthy those comments were, it was difficult to disqualify the efficiency of the film. In many ways, it felt like an American film but with more intriguing psychology and, above all, cinematography. The moderator compared some torture scenes with 24. Köbli followed up with the script to A Berni követ (2014) about a 1958 attack on the Hungarian embassy in Bern. The overall impression of Köbli’s work is that they always have a deft quality, but not necessarily a profound one.

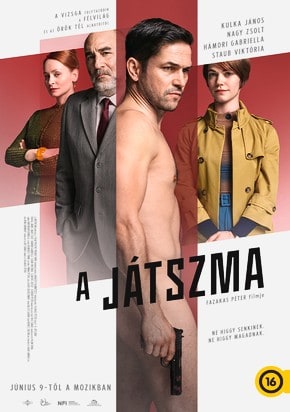

A Játszma

Flash forward to 2022. Péter Fasakas might be mostly known for his violent crime-comedy Para (2008). Now it was time to make A Játszma (The Game), based on Köblis’s script. In many ways, it’s a sequel to A vizsga, where several actors (János Kulka, Zsolt Nagy, and Péter Scherer repeat their roles from the previous film, even though their functions are different seven years later. The story about the student, Abigél (Viktória Staub), who gets a place to stay with Pál Márko (Kulki), seems clear enough with several problems involved, but it is merely the tip of a nebulous iceberg. The fact that the film is shot by András Nagy ensures that A Játszma is never boring to withhold.

There is still a slightly stilted quality to the film, which is quite adept at painting a picture of what life was like in the Kádár era. Technically, there is little to fault here, from the shades of Nagy’s lensing to Zoltán Kovács’ editing. The thespians do what they can with their material, as well. The main culprit is Köbli’s script, which rarely verges from the trodden path. The events in the third act feel like they were derived from the faraway corners of the Twists & Turns outlet section. Still, the film is fairly effective and never becomes dull or unwatchable, unlike many similar films nowadays.