Today marks the centenary of the birth of Miklós Jancsó, one of the giants in world cinema. Ten years ago, I was invited to attend his 90:th birthday party while his films were screened 24/7 in the beautiful Uránia cinema. I also had the chance to meet the director in person for a lively conversation. That was the year after his last feature; So much for Justice! (Oda az igazság 2010). It was a fascinating experience to see relatively rare Jancsó films with other spectators at 3 am. It’s impossible to sum up his legacy in a single post, but I will cover Jancsó’s trajectory through a selection of his films, some more well-known than others.

Is Cinema Inherently Primitive?

Jancsó repeatedly talked about what he called the poverty and limitations of cinema. What did he mean by that? His collaborator, Yvette Biro, quotes him in her book Profane Mythology. “It’s very simple. Cinema has limits that it can’t exceed. It can never go beyond catching the spectator’s interest to make a spectacle, and the framework of intellectualisation is restricted to it. Even the greatest films are primitive since their directness makes them aggressive. What happens in The Red and the White or any other of my films? People rush, they gallop, they fire shots, they run in all directions, and that’s it, that’s the maximum we can achieve.”

Biro sees his point but continues to point out how rich his (and others’) films actually are and that the “primitivity” can contain complex abstraction. She also points out that dynamism doesn’t exclude intellectualisation. 1The quote was spoken long before the phrase “Slow Cinema” was coined, I will use some of Jancsó’s films to point out some of the methods employed by the director to achieve this. It will be more of an overview than a detailed analysis.

I wrote about The Round-Up six months ago, which was the director’s major breakthrough. The year before, he made his third feature, My Way Home (Így Jöttem (1964). It’s the first of his films to carry all the Jancsó trademarks that would become persistent throughout his career. It’s set during WWll, and initially, we follow Jóska, who is trapped and released by Soviet troops, almost haphazardly in scenes that display the randomness of war. During the film’s second half, he will strike up an unexpected friendship with a Russian soldier. There are embryos of Jancsó’s famous long takes in several sequences courtesy of Támas Somló, and it’s a work that blends abstraction with a lyrical story about friendship.

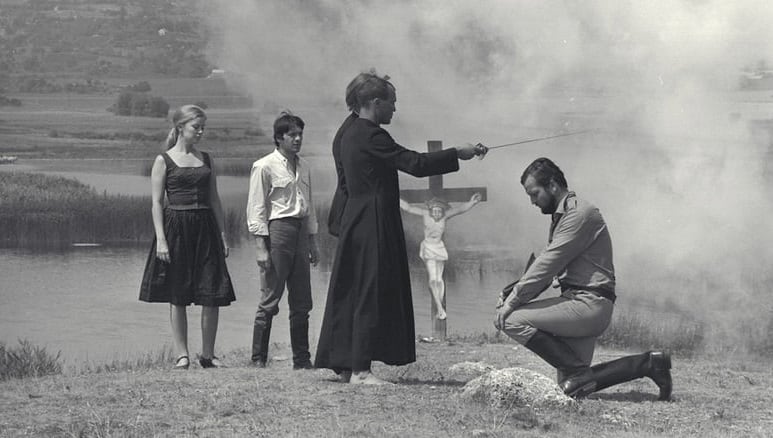

The latter would not be a typical element in Jancsó’s later films, where ideas of friendship or love are hardly approached. In The Red and the White (Csillagasok Katonák (1967), the closest we get is a nurse’s professional care who refuses to distinguish between the two fighting sides and helps everyone. The film was the first-ever co-production between Hungary and the Soviet Union, and the intention was to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Russian Revolution. Jancsó and his scenarist Gyula Hernádi (a crucial collaborator) had something else in mind, and the final film hardly celebrates anything. Instead, it is a cold, objective picture of war with its atrocities.

The film was initially stopped in The Soviet Union, then re-edited and screened there in a version as far away from a Director’s Cut as one could imagine. When the film was digitally restored a few years ago, both versions were provided, and it’s pretty droll to see Jancsó’s sharp, methodical work turned into a blunt propaganda tool. In the original version, the lyricism has yielded to the abstract inevitability of war.

There are no heroes or good guys, and occasionally, it’s not even apparent what is going on. In that way, it’s similar to Godard’s Les Carabiniers (1963). The Red and the White is one of Jancsó’s most famous films, and just like My Way Home, it provides an excellent starting point for his works.

In an early scene, an officer points his rifle at a man trying to run away, saying, “Why are you running? Are you trying to spoil my aim?” and then shoots him dead without any ceremony. That sets the mood for what will follow, where Jancsó never appeals to cheap sentimentality, and the final effect is all the more devastating for it. The tension between the formal beauty and the brutal acts makes for a startling work. The camera doesn’t perform the circular movements typical for the later films shot by János Kende, who opened up a new style variation for the director. The original title means “Stars, Soldiers” and is a more apt description of the film.

The Cinematic Ballet of Miklós Jancsó

Sirokkó (1969), known in English as Winter Wind, was the director’s second collaboration with Kende. His first Western European co-production is ostensibly the story about the group of Croatians plotting the assassination of King Alexander l in Marseille (which is incidentally Kende’s place of birth). However, the story is not the critical factor here, but rather the dazzling style. The film comprises only twelve shots with numerous complex camera movements, occasionally going from inside to outside down some stairs. Like many of Jancsó’s films, it demolishes the false dichotomy of style and content. The form is the content, like in all great works of art. It was followed in 1974 by Electra, My Love (Szerelmem Elektra).

By then, we are at the stage where Jancsó’s films came off as musicals. A choreographer is credited, and ideas are expressed as much by the characters’ movements and the camera as by the text of Laszló Gyurkó’s play on which it is based. Less famous outside Hungary than the Cannes winner Red Psalm (Még kér a nép 1972), this may be the summit of his oeuvre. It was difficult to see in decent quality for some time, but it was digitally restored a few years ago, and I was lucky to see it at Cinemathèque Francaise in 2015 during a retrospective that was cut short by the horrendous terrorist attacks.

Nobody would claim that the Italian co-productions were among Jancsó’s best films. Still, if one would choose only one to watch, it would be The Tyrant’s Heart (A zsarnok szíve, avagy Boccaccio Magyarországon 1981). The story of a naive Hungarian prince being retrieved from Hungary since his father died is told mainly in one setting. Apart from the elaborate camera movements, the whole thing has a theatrical feel, not merely because of Jancso’s usual style but because it feels stage-bound. Artifice is constantly, openly displayed. Actors make fun of their own death scenes (At one time, a character portrayed by Ninette Davoli says that he forgot the tomato, referring to the artificial blood).

The world’s a stage here, but it’s still unclear who plays whose parts. There seem to be numerous conspiracies ongoing, and will we ever find out who the actual culprit is? That question might keep the spectator pondering to the end and even beyond that. It’s a film full of trap doors and fakery, where the existence of objective truth is called into question. Later, during the eighties, Jancsó would make a cycle of films that used TV screens to depict some of the action. Sometimes, showing what we see for real, but on occasion, deviating from what we see and show something different or in a different manner.

The first of those films was Season of Monsters (Szörnyek Évadja 1987). It is set in the present time, which was rare for Jancsó then. It also has much more dialogue, especially during the film’s first half. The film starts with a TV interview with a professor who has just returned from the US. Said professor will then commit suicide and leave a letter for his mentor, who has a birthday party in the countryside. Initially, the modern setting (a hotel room, a speeding car) feels quite atypical for the director, as does the style. Once at the party, things feel more Jancsóesque with dancing, fires and naked women, but there are also new stylistic elements.

Season of Monsters is highly recommended and might surprise a spectator who only knows the director from his earlier films. The subsequent Jesus Christ’s Horoscope (Jézus Krisztus horoszkópja1989) and God Walks Backwards Isten hátrafelé megy (1991) both build on the same style, and the latter might take it as far as it can go. It’s really an arduous task to describe what is going on here. The Soviet conspiracy to get rid of Gorbachev and reclaim Eastern Europe is only one strand of the film that we see almost exclusively on TV screens. The film is also full of references to the director’s earlier films, and he appears notably by the end.

In 1998, Jancsó would get an unexpected audience triumph with the comedic The Lord’s Lantern in Budapest (Nekem lámpást adott kezembe az Úr Pesten). It introduced the two characters Kapa and Pepe, portrayed by Zoltán Mucsi and Péter Scherer. Because of the success, five other films would follow starring the duo. All of them are low-budget comedies with a fair amount of improvisation. Once again, Jancsó changed his style, and the reason he gave was that the world is so absurd now that the only reasonable reaction is to laugh about it. The first two films in the series are clearly the best.

So here ends my overview of one of the most fascinating film directors ever. Eleven of Miklós Jancsó’s films are available on Eastern European Movies. Some others are available on physical media. They are, unsurprisingly, not common on other streaming sites.